Why women should study theology together

The School of Theology’s central mission is to encourage and equip Christians to do theology together. We recognise, however, that the history of Christian theologising has been a heavily gendered one. Even now, there is significant gender imbalance among academic staff in Theology and Religion departments in the UK [a]. This represents an impairment to our goal of doing theology together, that is, with the wealth that diversity brings. In this essay, Charlotte Gibson discusses a way forward, not just by increasing the number of individual women writing theological books, but by women doing theology with one another for the edification of the wider Church. Charlotte is an ordinand at St Melitus, and host of the new podcast Women’s Theology Speakeasy.

“Mummy, is God a man?” asked my four-year-old daughter last week. I paused briefly before explaining that, no, God is not male, which is what she was really asking. The inevitable questions about Jesus and the Father followed, and I silently despaired that, more than two thousand years since Jesus, we are still communicating a male God to a church which is not dominantly male. [1]

Although for centuries men have been studying theology with other men (either in church, in groups or in reading theology written by men like the Church Fathers), the pages of our Bible are full of the experiences of women. Women who fight to save their people, women who lead, women who are raped, attacked and murdered, women who meet God in the wilderness, women who give birth to God, women who accompany Jesus, women who stay with Jesus, women who witness the resurrection, women who welcome the Holy Spirit, women who preach, women who run churches.

Women are called to do theology together

Women travelled with Jesus and funded Jesus’ ministry (Luke 8) and women were with him at the cross. All four Gospel accounts entrust the witness of the resurrection to women. In Matthew 28, the male guards faint as the angel descends to open the tomb; in Mark 16 the women flee in terror and amazement, and the differences in endings from the most ancient sources leave us unclear as to whether they ever tell their story (though the other accounts say otherwise); Luke 24 doubles the angelic presence and turns the women into theologians, having the angels asking questions and reminding them of what Jesus had told them about his death; John 20 makes the story earlier in the day, still dark, and Mary Magdalene is alone as she discovers the empty tomb, and alone when she meets the angel and Jesus. Although the discrepancies are numerous, the importance of the women’s part remains: the revelation of Jesus Christ’s resurrection from the dead was intended for the women before the men. Moreover, in the Synoptic accounts, the women are together when all is revealed.

Luke 24 is the most compelling evidence of women being encouraged to think theologically together, and this theme can be found throughout Luke’s Gospel. At the Annunciation (Luke 1) Mary, though perplexed, ponders and asks questions in her heart about the greeting of the angel and even asks a practical question. This is not an account of a woman whose obedience is based on being told what to do, but on understanding the message that God is sending to her. After hearing some more theological reflection from her cousin, Elizabeth (who has some experience in the area of miraculous pregnancies), she sings such great theology that it is repeated worldwide daily in prayer. Here, in the Magnificat (Luke 46-55), she is shown to be a woman who understands the very nature of God, singing of a God of justice and power, who sees the lowly and the poor. To go back to Elizabeth: her husband is literally silenced for the duration of the pregnancy, in order to give her the voice to name her child. It is an important detail that we must not miss, as only when he writes in agreement with his wife is he able to speak again. She is able to receive the message of God and believe, when he is not. Anna waits most of her life to see the Son of God presented in the temple. Although she does not speak, Luke makes sure we know that she is a prophet. Martha wishes for her sister to join her in serving, while Jesus urges her to join Mary in learning. At the tomb, the angel urges the women to theologically reflect and minister to the disciples. The very beginning of Jesus’ life and his death and resurrection are punctuated by faithful, theologically thinking women, and he encourages them in this.

In Acts and Paul’s letter to the Romans, we read of Prisca and other women running churches, Junia, a woman who is an outstanding apostle and Phoebe the deacon carrying a message on Paul’s behalf. Women’s theology is not an innovation.

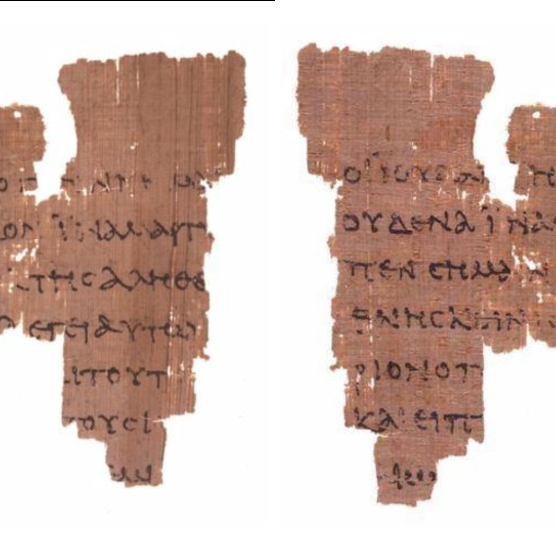

From the Triptych of Jan Crabbe, Hans Memling.

God has something specific to say to women, and through women to the Church

Women in the Bible are often spoken to by God when men are not present. Think of Hagar, doing theology in the wilderness, away from her oppressors and understanding who God is in light of her own revelation. Or the woman at the well in John 4, who Jesus provokes and discusses theology with her before sending her out to tell others about him. Or the Syrophoenician woman in Matthew 15, who presses Jesus and debates with him about the nature of his calling to those outside of Israel. God speaks to these women in unique ways, without a crowd of male disciples to be part of such events. In the book of Judith, we see a woman take charge of the situation at Bethulia: although we are not given the words from God (and indeed this is likely a work of fiction), she is portrayed as doing God’s will when the men stop listening. This is pertinent in a church which is seemingly aimed at men (while the women take care of the children, run Sunday School, serve tea and coffee etc), but in which there are more women than men worshipping on a Sunday. How do we, as women, do the work of God when it seems no one else is listening? What does it look like to act for God, in a church which speaks more about restrictions than the Holy Spirit moving us to compassion and care of the sick?

Conversely, consider Sarai, who enacts violence on Hagar; how can she be sure of the promises of God, when the revelation only comes to her via her husband? How differently might that story have played out if she had received the promise directly? This story is troubling for women, as Sarai does violence to Hagar, she repeats the violence already done to her in Genesis 12. Taken into the court of Pharaoh, to save her husband, Sarai is in danger while he profits from her ordeal and receiving oxen, slaves (perhaps Hagar is one of them), donkeys and camels (12:16).

Rebekah, in Genesis 25, receives prophecy from God that the twins in her womb will be in conflict, and which child is to serve the other. She alone receives this word from God, and she is forced to act alone to put God’s plan into action, deceiving Isaac in his old age so that Jacob can obtain the blessing meant for Esau. Although this is spoken to her from God, she will face judgment for her actions as the Church attempts to moralise the Old Testament. This is nothing new for women; if we take drastic measures to secure our own futures and safety by carrying rape alarms or something that could protect us in the event of being attacked, we are considered hysterical. Women who fight back against men that have abused them emotionally for years face trials for violence. Women who go back to work after having a baby should be at home, and women who stay at home are not contributing to the economy and should be in work. Would our testimonies be believed today if God spoke to us directly?

Women need to feel solidarity with characters in the Bible

There are numerous stories in Scripture which speak of abuse and violence towards women, which could potentially be damaging if read and reflected on alone. These texts do not appear in the Sunday lectionary, for good reason since preaching on such subjects would be almost impossible without knowing exactly who would be in the congregation and their experiences. Studying these texts together, while trying to cultivate as safe a space as possible, may allow women to think and reflect at their own pace, asking questions and drawing on their own experiences. Judges 19-21 is perhaps the most difficult text in the Bible, in which an unnamed Levite concubine is offered as a replacement for her husband, whom a gang of men have demanded to rape. She is raped until near dead, then she dies on the doorstep of the house. Her husband dismembers her body and scatters it throughout the land. Genesis 19 is similar in the way that Lot offers his daughters to men demanding to rape his visitors but is stopped by the angels beforehand. Jephthah’s daughter (Judges 11) is sacrificed to God by her father (she remains unnamed, an unfortunate casualty of her father’s unbelief), when he barters with God. She accepts her fate but asks for some time in the mountains to lament with the other women. It is a harrowingly calm account of a woman killed for no reason and her acceptance is reminiscent of the ways in which women are encouraged to accept their mistreatment in society: it’s just how it is, after all.

These stories are not just difficult in theory; not just problematic because they are hard to read. It is important to remember that women worldwide are still victims of rape and abuse. The ‘texts of terror’ that Phyllis Trible wrote about are relevant stories of real women; for many people approaching the Bible from places of pain, the Old Testament can feel more relevant than the Good News of the Gospels. It is not enough to talk about the goodness of God and our freedom in Christ when there is still such trauma and pain taking place on our streets and in people’s homes. Sometimes it is necessary for us to dwell in the pain, and learn to lament and process, rather than brush it under the proverbial carpet. The Church is very good about talking about abuse in superficial terms: we know that it is bad, and that God condemns it, but when do we take the time to sit and theologically reflect with the real experiences of women of the Bible? This is a bigger question and is not only aimed at women (in fact, men should study and reflect on these texts as well, for insight into women’s contemporary experience). But women deserve time and space to read stories which are simultaneously historical, contemporary and prophetic, with other women to whom the texts communicate the same message.

The Bible subverts what Western society considers womanhood

Women are expected to act a certain way and wear certain clothes for the benefit of other people. This starts at an early age, with marketing targeting young girls, teaching them that value is often in how they look. Then, women are judged for how they dress at every point. We are expected to get married, have children, be at home for a time, have a career, have sex regularly with their husbands (but not for their own pleasure). The truth is that what society expects is not possible for all women. There are numerous stories of infertility in the Bible (think Sarai, Rebekah, Rachel, Hannah and Elizabeth), all requiring and receiving Divine intervention. These stories are discouraging for women who are unable to conceive, as there is no story of a woman who remains childless. But there are also stories of women who do not live in their husband’s shadow; of women with no husband, who have a story in their own right. For example, take Judith (whom I have already mentioned): she is a widow who is dissatisfied with the leadership of the tribe and their reaction to the threat of the Assyrians. Taking matters into her own hands, she comes up with a plan and infiltrates the enemy camp. Ingratiating herself and her maid, she beheads the drunken Holofernes. She uses her sexuality as an asset, and he really thinks she wants to have sex with him. Winning victory for her people with only her maid by her side, she subverts the notion that women must act according to the will of the husband, or at least with his permission. Like Esther, her beauty is an asset and her sexuality is something to be celebrated; it reveals the weakness of this great army general who has dominated the world thus far. She is childless: we don’t know if she had wanted children, but it is beside the point, it is what she does that is really important. She could have remained a beautiful widow without being an Israelite heroine, indeed she goes back to it after leading her people in worship, but for once the focus is on her agency.

This theme is found throughout the Old Testament, in which many women are celebrated for using their sexuality for their good or the good of their people; in a patriarchal world it is the one thing that belongs to us. Think of Tamar, acting as a prostitute to secure her future (Genesis 38); or Rahab, hiding the spies in her brothel and saves her family (Joshua 2); or Esther, mentioned above, the most sexually pleasing wife in the harem gaining the King’s favour and stopping the genocide of her people (Esther); or Jael, who lures the army general into a false sense of security and saves her people from death and occupation (Judges 4). We normally focus on the virginity of Mary, and forget her bravery and her theological ability: who do we think taught Jesus the Scriptures? We obsess over Mary’s perpetual virginity, celebrating it or denying it in a way which reduces her personhood and agency; when will we talk about the political implications of the Magnificat in the same way? When will we recognise her ministry with the disciples at Pentecost (Acts 1-2)?

Part of my ministry as an ordinand is running Women’s Theology Groups in my placement parish. Twice a month, around 25 women gather together to study a biblical woman or a story which features significant female agency. We ask questions of the text, unhindered by the fear of saying the wrong thing. These groups are about giving the text back to the women, applying a variety of hermeneutical tools as we read and wrestle with that which makes us uncomfortable. But we are prepared for this, discomfort is present in the Bible; women wrestled theologically with God in the wilderness, with Jesus at the well and with angels at the tomb. The biggest task is making this a norm, and not relegating women to looking after children in church and serving coffee; as a church we are creating generations of Marthas, preventing women for discovering ‘the better part’ (Luke 10:42). For generations women have experienced Bible study through a patriarchal lens (literally with a focus on Abraham as opposed to Sarah and Hagar, or Isaac rather than Rebekah – arguably the women are the main protagonists through huge portions of these stories and yet they are forgotten). Many of us have forgotten the amazing part women play throughout Israel’s history, the Gospels and in the Early Church. It is time to reclaim our part through learning and studying together – maybe our own voices will be heard by others in the process.

So why should women study theology together?

Because the Bible tells us to do so. Because God has always spoken to and through women, God has always called women, God has always given us each other for solidarity, and God has always subverted what society dictates. God is not male, and maybe now the men will be ready to believe what we discover, in contrast to their disbelief of the women at the tomb.