Should clergy learn New Testament Greek?

Fr Sam Gibson argues for clergy to learn New Testament Greek, not only because it is useful but as askesis, spiritual discipline. Fr Sam is the assistant curate in the parish of Solihull. His book, The Apostolos, on Byzantine liturgical manuscripts is published by Gorgias Press.

“To imagine a language is to imagine a form of life” [1]. There are many excellent reasons for learning a language other than one’s own mother tongue. Doing so opens up horizons that would otherwise be closed. We are regularly reminded of the beneficial effects of language-learning for children, with all its concomitant social and intellectual advantages.

We also know that contemporary British society is quite exceptional, in comparison to most societies past and present, in being functionally monolingual. The ascendancy of a variety of standard English and its global dominance represents a victory (one might say) for our economic and social outlook, and also a bitter loss of voice – not just for the speakers of suppressed native languages, but also for the Anglophone would-be victors.

When it comes to spoken languages, I too am functionally monolingual. This is where most (though by no means all) clergy in these islands and in their sister churches begin.

After this I looked, and there was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages, standing before the throne and before the Lamb, robed in white, with palm branches in their hands. (Revelation 7:9)

Despite our monoglot tendencies, linguistic diversity plays a central part in salvation history, as we find it in the Bible. The confounded tongues of rebellious humanity at Babel (Gen 11) are reconciled in the life of the Holy Spirit (Acts 2), who brings understanding without eliminating difference. As the book of Revelation suggests, many voices will sing the Lord’s praises in the Kingdom, as many do now. The many tongues of the saints are like a prism through which the light of the gospel shines, each bringing a unique hue.

Occasionally, I feel left out of this diverse celebration. What joys sung and what mysteries uttered are there that remain undisclosed? English, for all its treasures, can be a beautiful prison. Richard Dawkins once wrote that for an English speaker to not know the Authorised Version would on some level make that person a barbarian [2]. Perhaps—but I think it is we, the Anglophones, who are really outside the gates.

It hardly helps that liturgy is now rendered almost exclusively in the contemporary vernacular, with an emphasis on basic intelligibility.Perhaps the preference on the part some young people for Latin Mass or dramatic glossolalia is a legitimate expression of the longing for sacred language, for the creative gratuity of God as displayed in the variety of human voices. It expresses the instinct, long reflected in human culture, that the word, spoken and sung, is a medium of divine revelation.

Created for beatitude, we seek a form of life outside the mundane in which new modes open up to us (praise, ascent, apophasis), voices denied to us by our first induction into the functionality of late-modern English. There is a kind of joyous rebellion against secularity, with its replicable consumer-oriented narrowness, which comes with bursting into an unfamiliar tongue. Incidentally, I think something like this is what may have attracted me to ancient languages in the first place.

All this is very general, you might say, and has little to do with learning New Testament Greek.

Yet we make a mistake if we look at biblical Greek courses outside of the wider cultural context in which our churches operate. To do so is already to make the mistake of seeing biblical Greek as a rarefied, abstruse, and impenetrable tongue; or worse, to see it as a sub-division of a particular kind of time-limited “training” (theological, clerical, leadership), which is at best an adjunct to superior portions of the curriculum, and therefore of lower priority than certain practical skills. This makes it all too dispensable when financial and time constraints arise.

Instead, we need to begin with some levelling of the ground. Clergy and ordinands who are already multilingual in some degree will likely recognise this: learning Greek should be no different, on one level, from picking up any other language. Nor should we underestimate the potential attractiveness of Greek, cultural and spiritual, to those raised and nurtured in the twenty-first century Anglosphere. It meets a longing that already exists.

Yet fewer students now than in previous eras seem to be driven by an interest in detailed exegesis, so we must begin where people are, with that desire for the transcendent and unfamiliar. This will take a change of perspective.

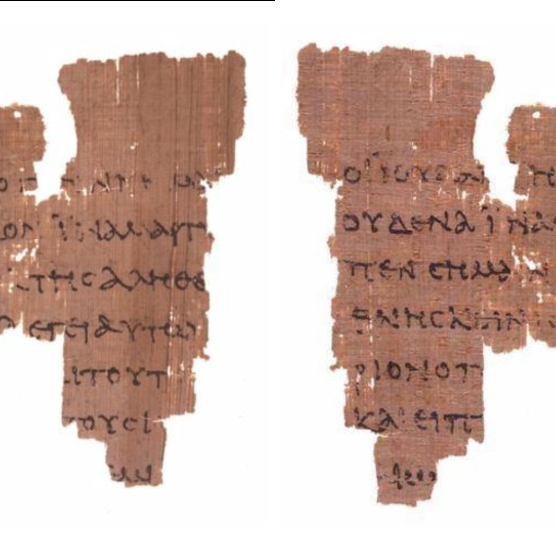

Rylands Library Papyrus P52 (verso, recto; Jn 18.37-38, Jn 18.31-33).

Currently, at least two things seem to distinguish biblical Greek from the kind of language-learning you might do at an evening class, or in preparation to go backpacking. Both distinctions ought to be advantageous but end up as stumbling blocks.

First, Greek-learning is focussed on a set text or texts (Scripture and associated literature), with a limited and specific vocabulary: the New Testament contains just over 5,400 different words. The rules of the game are clear, the idioms are set, and there is a voluminous literature able to guide the learner wherever she goes. This is not like a random conversation on the Paris Metro. Very little unexpected will happen, as far as the words themselves go. Not that this in any way diminishes the effects in the life of the student, but both the journey itself and the map are exceptionally reliable.

Second, and relatedly, biblical Greek is sometimes taught as if this made it a dead language. It is treated as an unchanging “classic” located in the first century, rather than an (important) snapshot of a living language, which has a continuum of its own from Plato to Byzantium and beyond.

From the beginning, both of these features enculturate learners into a kind of Greek-induced anxiety, and (let us be honest) a degree of boredom. I have observed talented musicians and mathematicians – both linguists in their own way – falter in the first semester of simple Greek, because they saw it as both as a dead, lofty “classic” and because they overestimated the actual content they were being asked to absorb.

So, a shift must take place in the way we discuss Greek and other biblical languages. It must be made clear that what is on offer is immersion in another “form of life”, which elicits commitment and is inherently formative. In both Classics and Biblical Studies there are excellent teachers who overcome these kind of initial difficulties, and provide experiences of this kind. There are also good scholarly, literary and historical reasons for learning Greek, as much as there are for any other language.

Having attempted to create a specifically cultural and theological background scene, I am not going to repeat the arguments made by other writers for general Greek-learning and the best methods involved, especially as I am not an expert in either area.

+++

What interests me here is why, given what has been said about language-learning, the Anglophone cultural background, and the perceived didactic barriers to learning New Testament Greek, those in or training for the priesthood should bother with it at all. Why should people called to priesthood learn some Greek?

First, language learning is part of a formational model of priestly life and growth.

Learning biblical Greek is, as has been suggested, formative. All Christians are called to askesis (training, discipline; the basis of the now narrowed English word ascetic) so that they can be conformed to the likeness of Jesus Christ, and so Christ can be formed fully in them (Gal 4:19). Those who are called to ministerial priesthood reflect this calling in a particular way. They are preparing soul, mind and body to receive the character of holy order and to live a life shaped by the cure of souls, the Eucharist, and the Liturgy of the Hours; all as participation in the holiness of Christ.

Anyone who wants to master a new skill knows it takes time, effort, perseverance of will and body, and commitment to a regular pattern. Praying the Office is similar. These actions require growth in the virtues, for sure. Mastering a new vocabulary and grammar is challenging, and at times can stretch our patience, obedience or humility. This in itself is a good enough reason for clergy and would-be ministers to undertake biblical Greek.

In seeing ministerial formation as askesis, a lifelong process of growth into maturity, we are rejecting a view of biblical language-learning as a one-off academic exercise, done to fulfil the requirements of university regulations. We are invited into the life of grace, which we know we require to minister in any capacity. At times, learning Greek is a hard test of this resolve to call upon God’s assistance.

Now some might object to this idea of askesis and say it is worldly, or that it lacks freedom in the Spirit. Yet anyone who has undertaken Church of England theological training recently will know that there are many disciplines to master, each of which is taken for granted. There are many terminologies to absorb, some kinder than others, whether that of clergy tax-returns or of Fresh Expressions. In other words, we already do asketics, so let us make sure that our labours bear lasting fruit.

I know an ordinand whose classmates were shocked when they discovered she was taking Greek, but not for credit. Her pathway did not allow her to gain academic credits from biblical Greek but she persevered. She kept at it, not only because she wanted to interpret Scripture accurately, but because she felt it was a liberation from a purely skills-based—some might say utilitarian—approach to priestly life. This is odd, on one level, because reading and writing a new language too is a skill (techne), but it is a craft that points beyond itself.

Given that it is also one of the languages of Sacred Scripture, and therefore bound up in God’s self-disclosure to humanity, we may also consider learning Greek an aspect of “priestcraft”, that particular art of forming a person to communicate the mystery of Jesus Christ.

Today priestcraft is very broad indeed including, for example, celebration of the sacraments, missional leadership and strategy, building preservation, and line management. Some of these non-linguistic disciplines can give us the illusion of mastery, especially in the social sciences, or else we can feel that we are adept at certain tasks in parish ministry, like pastoral care or fundraising.

In this context, the “otherness” of biblical languages is a powerful weapon against pride since they militate against that illusion of final mastery. Ultimately languages are what they are, greater than self and the milieu in which we undertake them, and they tolerate no clever tricks on our part. Once they get going, they are hard to fake. If we are serious about being formed, each day they will prompt us to learn more about ourselves as well as the texts they open up.

Second, and perhaps most obviously then, learning Greek aids in preaching and teaching of Scripture.

Since Vatican II an ecumenical consensus has emerged, grounded in the life of the early church, that parish ministers should be effective and fruitful exegetes and homilists. Whatever other charisms we might possess, there is no alternative to this, especially in the secular West. To some degree each of us needs to share in this craft, otherwise our attempts at apologetics, catechism, and evangelism will fail.

Ministering in Birmingham, I notice how our Muslim neighbours, and indeed many “secular” people, expect priests to be knowledgeable about the details of Scripture. Obviously Greek gives us, over time, growth in basic information about the words of the Bible and their semantic range, context, and translation. More importantly, immersion in a biblical language gives a sense of the whole shape of Scripture, its narrative and form, and its skopos (goal, purpose): the revelation of Jesus Christ. It becomes a house we are deeply familiar with, so much so that we can guide others around it.

Conversely, learning to read from a Greek Bible defamiliarises us from it. It provides a reminder that is written in a language, time, and culture not our own, that the light of the gospel has been refracted in other parts of the prism. We will become interested, for instance, in what Greek fathers have to say about passages and not just commentaries from last century, though these will help us too. We will learn to think with the mind of the Church in other places and times, and our preaching may become more consonant with the faith of the Church catholic throughout the ages, giving us a richness otherwise absent.

Reflecting the longing for a language of divine ascent, we learn to appreciate the particularity and distinctiveness of the sacred pages, and communicate a sense of wonder to those we minister with. Reading Greek can awaken in us a thirst for God in Scripture which draws others to encounter the gospel.

Finally, Greek reawakens in us the desire to make the Gospel known in all its fullness.

As I say, we have all adopted an askesis in certain things, whether for growth or decay. There is a real question for all those tasked with the ministry of the gospel about how we use our minds to glorify God.

Some things are important but as ends in themselves are distractions, like the relative merits of liturgical forms (old or new rite) or psychological models (leadership or personality types), and significant pastoral energy is often spent on these. The possibility of squandering our energy is open to us. I love to compare various parts of the Star Trek canon, but this will not directly aid me in living out the gospel.

Regular encounter with the Greek text of the Bible orients our practices, I believe, towards a continued search into the deeper meaning of the gospel and a desire to communicate truth.

Consider the recent translation debate between NT Wright and David Bentley-Hart about the world “spiritual” and its implications for present and future life [3]. Will we be embodied in the life to come, and in what way? What is heaven? What should the church and the body politic look like if one or the other has it right: what is the orthodox approach to bodies and souls, humans and angels? What will this look like in my parish, where bodies and minds are directed towards acquisition and consumption, or in yours where there is inadequate housing and exploitative work? These are not “academic” questions. All this from one word: pneumatikos.

And if I care about how pistis is used in various passages (belief in, loyalty to? [4, 5]) how will it shape my preparation of new Christians for baptism and confirmation? How will they live out the gospel I have been entrusted to deliver to them in their workplaces, homes, in the public sphere?

These things matter, and if we are to use our time in the acquisition of complex data, let us make it something like this – with deep applicability and ecumenical appeal – and not simply delving into a niche. Learning Greek, which is ultimately a lifelong process (I am hardly fluent myself), is about growth into these questions, shaping the ministry we offer. We can do these things in translation, and sometimes we must, but why not enter directly into the door open before us?

This is not the easiest path, pastorally or intellectually, but it is rewarding. As Origen discovered long ago, the words of Scripture themselves, even once known, can remain obscure, tough and challenging. Nevertheless, the learner who struggles prayerfully finds himself “called to the beginning of another way, so that … passing to a loftier and more sublime road, God might lay open the immense breadth of Divine Wisdom.” (De Principiis IV:1:15)

Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical Investigations(G. E. M. Anscombe, Trans.). Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell.

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2012/may/19/richard-dawkins-king-james-bible

Bates, M. W. (2017). Salvation by allegiance alone. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

Morgan, T. (2015). Roman faith and Christian faith: Pistis and fides in the early Roman empire and early churches. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.