Guest post: Which Old Testament?

This week, we have a guest post by Susannah Peppiatt, who has just completed her BA and MSt in Theology at Keble College, Oxford; she is now headed for a Pastoral Internship with Hereford Discover. While at Oxford, Susannah was Head Server at St Mary Magdalen’s.

I was recently looking for an audio Bible app for my phone and came across a review of one particular app which declared, rather fiercely, that ‘This version can send you to hell’. The reviewer objected that

‘KJV Jesus says we must be “converted” and this ESV says “forgiven”. This is huge. Converted and forgiven are two different words. Being born again and forgiven is not even close. This doesn’t save NO ONE. Garbage.’

I probably wouldn’t go so far as to declare the ESV to be ‘garbage’ myself, but this upset reviewer is right about one thing: how we translate things matters. If we believe, as the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion tell us to, that ‘Holy Scripture containeth all things necessary to salvation’, then what Scriptures, and what translation, we are reading is important, and it may not always be as straightforward a question as it seems.

The books now considered Scripture in the Christian Canon were composed over a span of about a thousand years, with some material potentially having roots as far back as the 10th or 11th centuries BCE, and some as recent as the end of the 1st century CE. By and large, what we now call the Old Testament was composed in Hebrew and what we now know as the New Testament was composed in Greek. However, the first language in which a story was told is not necessarily the language in which it should always be kept. The hymn ‘Let all mortal flesh keep silence’, for example, was originally composed in Greek, and Gerard Moultrie’s translation found in the New English Hymnal is not exactly a wholly ‘literal’ translation, but it is the one we know and love and the one that has seeped into the consciousness of many hymn-singers over the years.

+++

Around 3,000 years ago, the Hebrew people created the first alphabetic language by doubling the consonants heh, vav and yudas vowel letters. In English, this would be roughly analogous to using the letter h as a; the letter y for i and e; and w for o and u. The use of these vowel letters made it a lot easier to read and write with less training, because vowels allow us to understand a word far easier if we are not professional scribes or not native speakers of the language. For example, although it would be relatively easy for us to recognise “Lndn” as London, knowing that the vowels were not shown, you can see how quickly this might get confusing once we enter full sentences. Timothy Law gives a good example: “Jn rn t th str t by brd” could be anything from “Jon ran to the store to buy bread” to “Jane, I run to thee, a star to obey, a bride!” The comparison to English is, of course, quite unfair because English is more dependent on its vowels than Hebrew (we have whole words that are just one vowel, for example, like ‘I’ or ‘a’), but this may give some idea of the sort of exercise that the Masoretes were attempting to carry out in the 7th and 8th centuries CE when they set out to standardise the Hebrew Scriptures and aid reading by adding indications of vowels and other grammatical structures. These grammarians likely spoke Arabic natively, not Hebrew, and indeed, it seems likely that Hebrew had become an exclusively liturgical language somewhere between the 2nd and 6th centuries CE. Of course, the vowel-letters mentioned above would have made it quite a lot easier than it might otherwise have been, but because they were a relatively recent addition to the alphabet and not strictly necessary, these vowel-letters were often omitted, especially in manuscripts where there was a desire to preserve a sense of antiquity – even today, the central bus station in Jerusalem spells “Jerusalem” as ירשלמ, without the final yud which would be more conventional in modern Hebrew.

The creation of the Hebrew texts from which we translate the Christian Old Testament, then, should already be considered, if not a translation, then at least an interpretation. Which is all just to problematise the straightforward assumption that Hebrew means older means better.

But if not Hebrew, then what?

Well, while the oldest complete Hebrew manuscripts we have date from no earlier than the 9th century (CE), we have a smattering of complete Greek manuscripts of the Old Testament from the 4th and 5th centuries CE. However, the date of the exact copy of the text is, in many ways, less interesting than the date that it came to take the form in which we know it. Which, for the Greek, means around the 3rd to 2nd centuries before Christ. That is, almost a millennium before the Masoretes were working, a translation of the Hebrew Scriptures was being made in and around Alexandria, which later came to be known as the ‘Septuagint’, from Latin for ‘seventy’, in honour of the legend that 72 translators (six from each of the tribes of Isreal) worked together on translating the Pentateuch at the request of King Ptolemy Philadelphus II. One of the versions of this legend, passed on by Philo in his Life of Moses, tells us that each of the translators was separated into their own cells to work on their translations, and when they later joined back together to compare translations, they found that each and every translator had come up with exactly the same rendering of every passage. Other versions of the legend are more understated, but this version best conveys the claim that the Septuagint was not so much a faithful translation as an inspired translation – which allowed Philo (and later the New Testament writers, and Church Fathers) to draw heavily on the Septuagint as authoritative even where it did not agree with the Hebrew text.

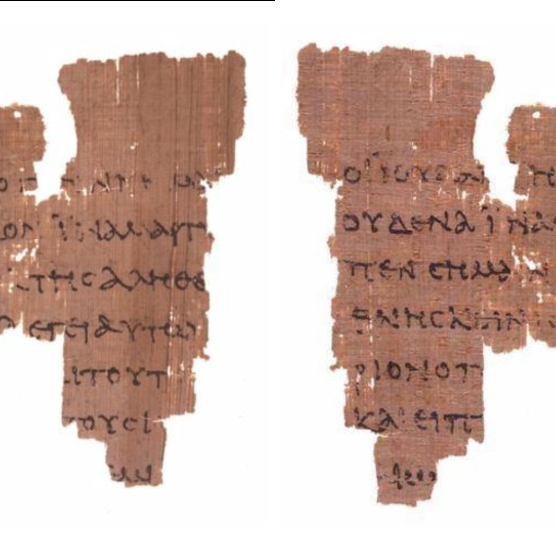

Fragment form from Nahal Hever (8HevXII gr). Image from Wikimedia.

Indeed, there is no shortage of places where the Septuagint and the Masoretic Text disagree. If the Septuagint is viewed as simply a translation of the Hebrew text that we have today, then it would turn out to be a rather shabby translation that doesn’t even cover all the text – missing, as it does, a sixth of Job and an eighth of Jeremiah among other things, as well as containing extra books (some that were not even originally written in Hebrew), and changing the order and groupings of the books included. We should also be aware that just as the styles of different books in the Old Testament vary quite a lot, so too do the translations, some of which are extremely literal translations that try to preserve even Hebrew syntax and word order, while others are more focused on rendering it into elegant and readable Greek; a variety which suggests, despite the fun legend that I told a moment ago, that the Septuagint was probably translated in sections, as and when (and where) the need arose.

If we were reading the Old Testament on its own for purely academic interest, then all of these differences might not be all that important, but as Christians, which Old Testament we use makes a difference to how we understand God.

+++

When I was in my early teens and aggressively suspicious of strange ideas like the Virgin Birth, I remember learning, to my delight, that it was a doctrine based on a mistranslation. Matthew quotes Isaiah as saying ‘Look, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall name him Emmanuel’ (Matt. 1.23), but if you flip back through your Bible, you find that the bit of Isaiah here quoted says ‘Look, the young woman is with child and shall bear a son, and shall name him Immanuel.’ (Isa. 7.14). Vindication! The Virgin Birth was an unnecessary doctrinal mistake based on a mistranslation and could be done away with!

But how does Matthew see ‘young woman’ and read ‘virgin’? Well, he doesn’t. Matthew is here following the Septuagint in using the Greek word parthenos (παρθενος), which is closer to ‘maiden’ in English, with all its young and virginal connotations, while the Hebrew has instead the word almah (צלמה) for ‘young woman’, with no more than a slight implication of virginity due to most young women of the time being virgins.

Many more examples can be enumerated from the Gospels, Paul and indeed the Church Fathers, but this is perhaps the clearest instance in which the Septuagint allows for a much more Messianic reading than the Masoretic Text would allow.

Which is, perhaps, no accident.

After all, it wasn’t only the Christian canon that was being solidified around the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, but also the Jewish canon, and the fact that the pesky Christians kept reading Messianic prophecies into their texts was, let’s be honest, probably quite irritating for Jewish communities with no interest in this Jesus fellow. Thus, that textual or interpretative traditions that prioritised non-Messianic readings might well have been ‘naturally selected’ among Jewish communities exactly at the same time as the opposite trend is happening in Christian circles, should be unsurprising.

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls in 1947 also help to flesh out this picture. These texts found in caves near Qumran are largely biblical texts or commentaries on biblical texts dating from the 3rd century BCE to the 1st century CE. Generally speaking, these texts look exactly the same as the Masoretic Text only about half of the time, and in many of the places where they disagree with the Masoretic Text, they contains a reading much closer to that found in the Septuagint. Which is to say, the Hebrew text of the Bible, like any ancient text, was not entirely uniform or stable in this period, and it is possible that the Septuagint and the Dead Sea Scrolls are both witnesses to different and not necessarily less valid textual traditions of Scripture.

As the Church spread in the first few centuries CE, the Septuagint spread with it, being translated into new languages as Christianity spread to new lands, among them Coptic, Armenian, Latin, Gothic, Georgian, Ethiopic, Syriac and Slavonic. For the Western Church, the most important of these was Latin, the language of the Roman Empire and the language which would remain the language of the Catholic Church for well over a thousand years. The Latin translations, however, were quite bad and incredibly varied, to the extent that St Augustine laments in a letter that “The variations found in the different codices of the Latin text are intolerably numerous; and it is so justly open to suspicion as possibly different from what is to be found in the Greek, that one has no confidence in either quoting it or proving anything by its help”.

In an effort to combat this shambles of Latin Scripture, Pope Damasus commissioned St Jerome to make a new translation of the Bible into Latin. Pope Damasus, of course, intended this to be from the Septuagint as all previous translations had been, but Jerome agreed to make a translation only if it could be translated from the Hebraica Veritas, or ‘Hebrew Truth’.

Until this point, with the exception of a small Syriac community, every Christian community had known the Scriptures through the Septuagint, whether directly by reading it in Greek or through one of its many translations. Unsurprisingly, then, given some of the considerations discussed above, Jerome’s translation was treated with suspicion by many at first, especially in the East, but by the end of the 6th century (nearly two full centuries after Jerome had completed it around 405), it became standard in the West and would remain so until the Reformation a thousand years later.

It would, of course, be impractical to attempt to reintroduce the Septuagint as the standard Christian Old Testament today – but, practicality aside, re-adopting the Septuagint in the West could allow for the unity of the Old and New Testaments to be shine through more clearly, and would put us in good company with the Fathers of the Church and the Eastern Orthodox, who continue to use the Septuagint, either directly in Greek or as the basis of its translations, to this day.

Bibliography/Further Reading:

Law, T. M. When God Spoke Greek: The Septuagint and the Making of the Christian Bible. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Hoffman, Joel M. In the Beginning: A Short History of the Hebrew Language. New York: New York University Press, 2004.

A New English Translation of the Septuagint: And the Other Greek Translations Traditionally Included under That Title. New York: Oxford UP, 2007. Available freely online at: http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/nets/