Easter series -- “Why do you seek the living among the dead?”

This Eastertide, we present a series of reflections on the events of Holy Week. Today's reflection is by Fr Peter Groves, and is taken from a homily at St Mary Magdalen's, Oxford.

Religion is once again a fashionable subject, at least as far as the media is concerned. It is not surprising to find religion close to our front pages or featured early in our news programmes. Theology, on the other hand, is less and less fashionable; something we hope the School of Theology will address. What I mean by distinguishing religion and theology here is that the media’s current love affair with religion is a love affair on their own terms: religion needs to be juicy, controversial, full of soundbites. It mustn’t ask difficult questions, it mustn’t challenge the orthodoxy of self-interest and, most important of all, it mustn’t say anything to suggest that media manipulation of the truth is not a good thing. So for example it is with impunity that our newspapers can lay into the former Archbishop of Canterbury for saying things he hasn’t said, and then blame him for their mistake on the grounds that they find him difficult to understand. Perhaps they’d do better if they paid attention rather than seeking it.

So I am surprised whenever I find theology, genuine theology, featuring as an item on the radio, as I did some time ago on the Today programme on Radio 4. An American professor called Gary Habermas had been touring a series of workshops on the evidence for the resurrection of Jesus, and these have been conducted by the then Bishop of Durham, Tom Wright formerly of almost our parish: Worcester College is the other side of the road from the parish boundary. This is a highly refreshing development. The resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth is, Christians claim, an historical event. Those who dismiss it as fantasy ought to pay attention to the evidence. Few people do. In fact, that evidence is remarkably impressive, and as much for what it doesn’t say, as for what it does, because if one were to make up a story of resurrection – as critics of Christianity claim happened – then it wouldn’t look anything like the stories we have. One simple point is that you wouldn’t, in the first century, make up a story that depended on the testimony of women. How ironic, since we all know that men are far more prone to exaggerate.

Two things are essential to a Christian doctrine of the resurrection. The first of them is that the resurrection of Christ was something real. The second is like it, but different: the resurrection of Christ is something real. When I was a pious teenager I had a poster in my room in which a man stood by a newsboard on which were the words “Jesus Christ has risen”: someone had replaced the word “has” with the word “is”, and added the word “today”.

Attending to the evidence for the resurrection of Jesus is important and necessary, but, as Professor Wright would be quick to point out, it is nothing like the whole story. If I find myself bogged down in evidential questions about what exactly happened at precisely what moment I will find that I am contradicted by the New Testament itself, which is insistent that Jesus really rose from the dead, and equally insistent that it does not concern itself with unknowable details. In John’s gospel, which we hear on Easter Day, Mary Magdalen goes to the tomb, and sees that the stone has been rolled away and the tomb is empty. She runs to tell the disciples but what she tells them is not “he is risen” but “they have taken him away”. Her reaction is perfectly natural. If we encounter an empty tomb or a dug out grave, we are not likely to think that someone has risen from the dead, but that someone very much alive has taken away the body. Even when Mary meets Jesus it is not until he calls her by name that she perceives what has really happened. It is the presence of Jesus, not his absence, which tells her and us that he is not dead but alive.

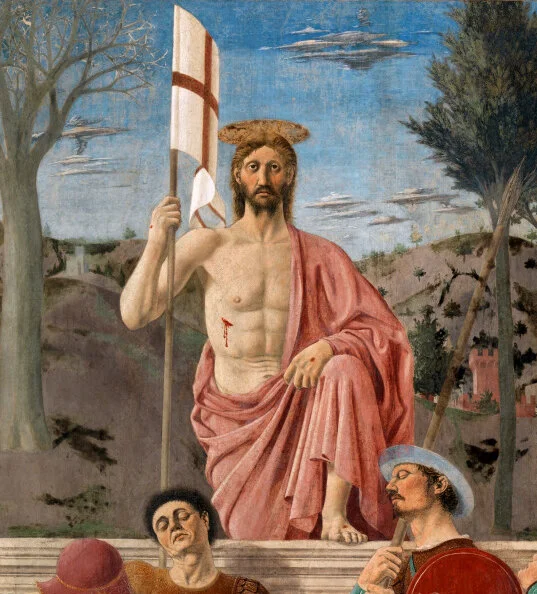

Ghislaine Howard. Study of the Empty Tomb.

In Luke’s gospel Mary and her companions are greeted met by two mysterious figures who make this very point by asking them “Why do you seek the living among the dead?” The resurrection which we proclaim is the final and ultimate sign that our attempts to pin God down, to control him, wrap him up in a place, a book, a hierarchy and even a person, will never be enough. Having fallen flat on our faces when we thought that love was dead, we are now confounded one more wonderful time by the refusal of God to play games, to gloat in his victory, to stand and take the applause which we are all too ready to give.

The women, and the disciples, find a tomb which is empty. Jesus has gone before them. They have, then, a choice: hang around, scouring the empty tomb, going in and looking at all there is to see, focusing on the absence of a body rather than a presence: or acting on that injunction to follow, to go after Jesus, to allow themselves to be led not just home – for they, remember are Galileans – but also abroad, because Galilee is also the home of the Gentiles, the symbol of the gospel as it spreads from Jerusalem across and around the entire created world.

Why do we seek the living among the dead? To look only at the empty tomb is to commit the dangerous mistake which we have considered throughout this week. I can look at the events of Jesus death and resurrection simply as a set of historical events. In so doing, I see them at a distance and make no connection between the events themselves and myself as their witness. Or, on the other hand, I can recognise that the resurrection of Jesus is, yes, an historical event but also and far more importantly an eternal event, the eternal event, the decisive moment of human history in which the life giving presence of God ruptures the world that we thought we knew and remakes it, renews it in the risen life of Christ which you and I are invited by grace to share. The risen life of Christ is here, there and everywhere, present us for all to see, in the vital and energetic life of the world around us, in the beauty of the created order, the magnificence of human endeavour, the resonance of music and the arts, the generosity of our neighbours, the love of those who make our lives what they are.

But this is not a substitute, not an alternative, not a mere symbol for the resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth. Rather it is the effect of that real resurrection. The resurrection of Jesus was and is real and ought to be the basis of everything which we call life, precisely because the presence of Christ is as real, as life-giving, as triumphant, as enduring in your life and mine as it was in the lives of those we call his disciples.

So what are we to do with this good news? Sit back, and congratulate God on a job well done? Or do something about it, act upon the gospel, take seriously the instruction to go and meet Jesus? For he is ever present, ever ready, ever waiting to meet us in every corner of the wonderful mess that we call our lives. Life, after all, is what Easter is about. And life, as they say, is for living.