Easter series -- “God is gone up with a merry noise”

The Revd Katherine Price writes on the the Ascension. She is Chaplain of The Queen's College, Oxford.

Ascension roundel, the Chapel of The Queen’s College, Oxford

When I first arrived at the Chapel where I now serve as Chaplain, I was somewhat dismayed to find it dominated by this image of the Ascension. Not that this image, populated by angels rather than the more conventional baffled disciples, is instantly recognizable as a depiction of the Ascension. That in itself is oddly appropriate, since this key episode in the Christian story is prone to being confused or conflated with others. The New Testament scholar and former Bishop of Durham N. T. Wright provides a good analysis of this, and why it’s a problem, in his book Surprised by Hope. There, he argues that the prophecy of the Son of Man "coming on the clouds" is a description not of the Second Coming but of Jesus’s arrival in heaven at his Ascension – precisely what is depicted here.

So why my dismay? Firstly, because the Ascension caused the first (and I think only) time I have been called a heretic in a theology class. The Ascension represents the "taking up" of our human nature into the very heart of the Trinity. I was trying to get my head round how that doesn’t equate to a change within God’s self. In case my former tutor is reading this, I will just say: it doesn’t.

Secondly, because I was reminded of a question asked by a child during a school trip to my curacy parish. Having heard that Jesus died and was resurrected, he asked where Jesus was now. Had he died a second time? Smart kid. “Ah – no – the Ascension!” say I, brightly. Relief at having a ready answer quickly gave way to panic at the prospect of trying to explain the Ascension without giving the children the idea that heaven is somewhere "up there", and that Jesus has shot off like a rocket and is now in orbit round the Moon. It also left me uncomfortably wondering whether the Church might have come up with an entire Feast just to answer smart-alec questions from kids about why we don’t see Jesus any more.

Stained glass window in the Chapel of The Queen’s College, Oxford

The Ascension as vertical take-off, depicted in this other image from the Chapel more conventionally and complete with dangling feet, comes of course from Luke’s description at the beginning of the Acts of the Apostles (1.6-11). Here he elaborates on the rather briefer and more ambiguous account at the end of his Gospel. As with his account of Jesus’s baptism, in which the Holy Spirit goes from being merely "like a dove" in the other Synoptics to having the "bodily form" of a dove, the modern reader might wish Luke had been content to leave things a little less concrete. The "triple decker universe" may be an unfairly crude characterization of how previous generations viewed the relationship of Earth and Heaven. Nevertheless, it seems to have been accepted that human beings might go bodily into heaven, and indeed return; Elijah is only the most obvious biblical example. Intriguingly, Islam finds both the Ascension of Jesus and his second coming easier to swallow than his death and resurrection (see for example, Sūrat an-Nisāʼ ayat 157-158; Hâdith 656). On the most basic level, the Ascension is a promise that Jesus is still around and will be back: “you will see him coming in the same way you saw him go”.

But the difference between Elijah (and indeed the Jesus of the Qur'an) and the Christian belief in Christ’s Ascension is that Jesus ascends in a body that has already been transformed by resurrection. This is not a body bound by familiar physical laws in a physically up-there heaven. It is a body which, through the Ascension, is now made immediately present to us in any place through the blessed Sacrament.

Luke is the only gospel writer to include an account of the Ascension. John's Gospel, however, also alludes to it in a number of places, not least in Jesus’s words to Mary Magdalene by the garden tomb. John does not follow the neat schema which gives us our liturgical calendar of crucifixion – resurrection – ascension – Pentecost. Rather, he refers to a "lifting up" which encompasses the significance of the crucifixion, resurrection, and ascension.

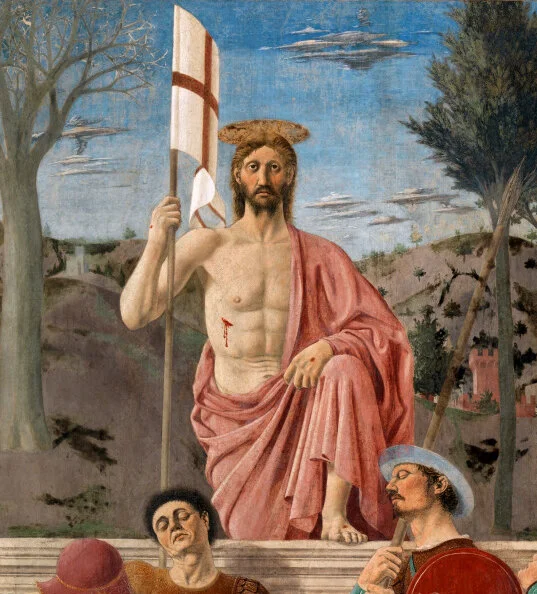

In the same passage, Jesus tells Nicodemus, “No-one has ascended into heaven except the one who descended from heaven” (Jn 3.13). But that does not mean the Ascension is some kind of reverse Incarnation. On the contrary, it means that the Incarnation is a one-way process. Having once been made man, the second person of the Trinity does not "disincarnate"; he is not, if you like, sucked back out of the man Jesus of Nazareth and tucked neatly back into heaven where he belongs. In the Ascension roundel at the top of this essay, you can just about see the marks of his wounds. The human body of Christ – born of Mary, crucified at Golgotha, and resurrected on the third day – is ascended and glorified and remains in eternity. As we pray during the mass, at the mixing of water and wine, we are lifted to share in Christ’s divinity just as he stooped to share in our humanity.

And the Ascension is a triumph not just for us in our humanity, but also in a sense for God himself. Jesus is not only received into his father’s arms but lifted up, set on his right hand. “God is gone up with a merry noise” – here we borrow the symbolism of Psalm 47, God returning in triumph to his Temple. This is not just about Christ returning to the Father, but God himself returning to his rightful place of kingship over his people. It is this heavenly perspective which is depicted in the ceiling painting: “God’s in his Heaven, all’s right with the world”.

But there is something to be said too for the earthbound perspective of the image in the stained glass window - for all the literalism of Luke’s account, and for all the flailing feet. Not mentioned in the scriptural account, but clearly visible here between the two angels, are Jesus’ footprints. Like the empty tomb, they are a kind of visible absence. Luke focuses us on the disciples, Jesus’ friends, now deprived of his presence once again.

Both in Luke’s gospel and in John’s, Jesus’ bodily absence is associated with the promised coming of the Holy Spirit: “It is to your benefit that I go away” (John 16.7). We must take care here not to fall into modalism: that is, into suggesting that the Spirit is Jesus’ presence in a new form, or that the ‘age’ of the Son has been succeeded by an ‘age’ of the Spirit. Pentecost does not follow immediately on Ascension, just as Easter Sunday does not follow immediately after Good Friday. Rather, we are given time to experience the absence of God, or the absence of our previously familiar ways of knowing him. “Do not cling to me,” Jesus tells Mary (Thomas, whose need is different, is invited to touch). Throughout his ministry, Jesus has been leading his disciples towards this maturity: into letting go of their dependence on his visible presence and their limited understanding of who he is, and yearning instead for the living God in all his fullness.

And so we see them, gazing up into heaven – and then turning, and going to do God’s work in the world.