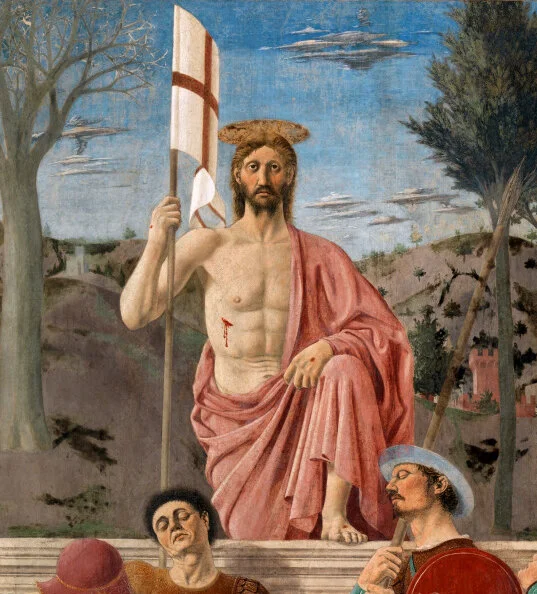

Easter Series -- "There is nothing to see here"

This Eastertide, we present a series of reflections on the events of Holy Week. Today's reflection is by Fr Peter Groves, vicar of St Mary Magdalen, Oxford.

Crowds are important in Holy Week. On Palm Sunday, as we recall Jesus’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem we carry our palms to remind us of the crowds who welcomed him into the Holy City, with blessings, prayers and shouts of praise. On Maundy Thursday, when we strip the church and leave in silence, we become those crowds of people who have now abandoned Jesus to his fate and leave him entirely alone. On Good Friday we retell the story of the crucifixion with the relentless baiting of the mob which is whipped up in the presence of Pilate, baying for the blood of the Galilean preacher, and screaming for the release of a murderer in his stead. There was nothing private about crucifixion – it was intended as a very public spectacle, so that the crowds of onlookers would see the fate of others and think twice about challenging those in authority.

Crowds feature rather less in the stories of the resurrection. True, Paul makes reference to the risen Christ appearing to five hundred of the brethren, but the gospel narratives are small and intimate. Perhaps this is not surprising. Death, particularly death which involves blood and gore, torture and agony, is exciting, macabre, even glamorous. Our ghoulish desires to look upon the misfortune of others have changed little over the years, as anyone caught behind a traffic accident will testify, as they watch the vehicles on the other side slow down for a better look at the carnage. Life, it seems, is of little interest. Crowds love death and destruction, and those who have the misfortune to deal with it directly more often than not have to usher those crowds away with the expected but not entirely truthful words, there’s nothing to see here.

“There’s nothing to see here.” It’s a phrase which is unlikely to persuade us to do as the speaker requires. There’s nothing to see here means to us “there is very much something to see here, but I’d rather you moved along and didn’t see it”, and thus our earnest desire is to stay at the scene of the incident, stretching our necks beyond the police cordon and catching a glimpse of something, anything, which might reveal the reality that the authorities would rather we did not witness. There’s nothing to see here is intended to make us go away, but instead it keeps us rooted to the spot, precisely because we know that it isn’t true.

What if it were true, however, that there is nothing to see? Would we still be gawping in wonder? I doubt it. What we’re after is death, not life; a broken arm is more interesting than a healthy arm, a bloody face more gripping than one smiling. Life does not find us in the newspapers, love rarely gets us on TV.

Imagine, just for a moment, that the worst has indeed happened, that the disaster industry is in full swing, that each of us has undergone something unimaginably awful, something which seems to have brought an end to all the happiness we could ever envisage. Imagine also that in the moment of that greatest darkness, someone told us that everything was all right, that if we would only come and look we would find that all was well, darkness was light, the situation had been turned upon its head and that everything was indeed all right.

If we imagine this we begin, only begin, to place ourselves in the gospel stories on that first Easter morning. Life itself had come to an end, the promise of the kingdom, the joy of forgiveness the presence of God himself had been snuffed out before their eyes and nothing could now come to any good. Yet, despite all this, they have a memory, a memory of someone telling them that everything would be all right. Without anything better to do, because they have no idea how to move on, they go to the place of darkness and burial and attend to the business of death – death which is now the order of the day. But instead of death, what do they find? Nothing at all. Nothing. Not a body, not a man, not a corpse, not even a tomb – it had been a tomb, but now it’s empty and has become simply a space, an absence, a nothing. In this case, there really is nothing to see.

Not only that, but the fact that there is nothing to see suggests to them that they were wrong to think that everything will be all right. Because it is not everything which is all right, it is nothing. Nothing at all is right. Even the last object to which they were clinging, the lifeless body of the one in which they had placed so much hope, even this last certainty, the certainty of death, has been taken from them. There is nothing to see, and nothing is all right.

Everything will be all right. There is a tendency in Christianity to see the resurrection as separate from the rest of the gospel, as if the ministry, teaching and suffering of Jesus were an unfortunate necessity which enable us to arrive where we are today. If we think this way, it is no wonder that when we come looking for Jesus we find nothing at all. Everything we celebrate during Holy Week, all the anguish and suffering of the Word made flesh, is the result of the love of Christ poured out into and through a human life to its utmost, to the point of the surrender of that life itself. The love of God will not be contained and won’t be controlled, so that even when we think we have brought it to an end, even when we are satisfied that we have squeezed the life out of it and shut it securely up in a stone cold place of safety, it cannot help but live. The love of God bursts from the tomb of Christ as surely as the presence of Jesus does not hang around for applause or congratulation but goes before the disciples into Galilee, instructs them to follow, demands them to act in response to the love which has recreated everything by reducing it to nothing and bringing it once again to life.

There is nothing to see here. That is the whole point. Everything will be all right only because nothing will be all right, because in the miracle of God’s redemptive love everything has become nothing, so that nothing – the empty tomb, the absent body of Christ – has become everything, more than we could possibly imagine, everything that mortal life has ever wanted and so much more. The love that we thought led only to death leads not just from death to life, but through death to new life, to a life which is lived in the knowledge that death is nothing at all, in the knowledge that nothing at all is death; because Christ is raised from the dead, is raised, is present, lives, gives, speaks, loves, there and then, here and now, in you and in me and in every created thing, because everything was brought to nothing so that nothing will finally be everything.