God and Emotions series -- "Does God Suffer?"

In this fourth instalment of our on-going series on God and Emotions, Fr Simon Cuff writes on whether or not God suffers. Essays on this theme will be published monthly.

‘This is the decisive difference between Christianity and all religions. Man's religiosity makes him look in his distress to the power of God in the world; he uses God as a deus ex machina. The Bible, however, directs us to the powerlessness and suffering of God; only a suffering God can help. To this extent we may say that the process we have described by which the world came of age was an abandonment of the false conception of God, and a clearing of the decks for the God of the Bible, who conquers power and space in the world by his weakness. . .’ -- Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Letters and Papers from Prison

There are many enticing delights in the basket of heresies available to those who would try to follow Christ. All heresies have at least one thing in common. They’re a simple, and usually attractive, means of making some aspect of the Christian faith easier to swallow than what’s taught within Christian orthodoxy. They often seek to smooth or iron out frustrating tensions that Christian orthodoxy seems quite happy to let stand. All heresies also almost aways have unintended consequences - they make an aspect of the faith easier to swallow, but can cause problems further down the theological line.

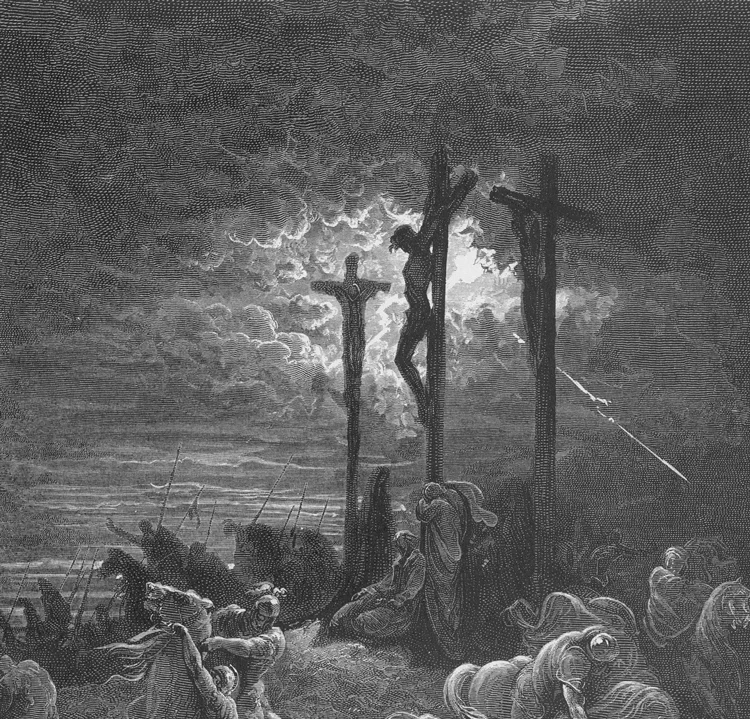

One of my favourite heresies - for its name, if nothing else - is the heresy of ‘patripassianism’. This is the view that the Father suffers on the Cross. It’s easy to see how we get here. The Son suffers on the Cross. The Son is God. The Father is God, ergo the Father suffers on the Cross. Christian orthodoxy says no here. We’re permitted to say that God died on the cross (in fact, it’s rather important we do) but not the Father. If we can say so at all, it’s the Son who we say suffers on the cross.

Christian worries about how much we can say God suffers go deeper that worries about the heresy of ‘patripassianism’. A tenet of the Christian doctrine of God is that he does not suffer. The technical term for this is ‘impassible’. We read of this divine impassibility in Scripture - in God 'there is no variation or shadow due to change’ (James 1.17) If he suffers, he is liable to change. For God to be passible is impossible.

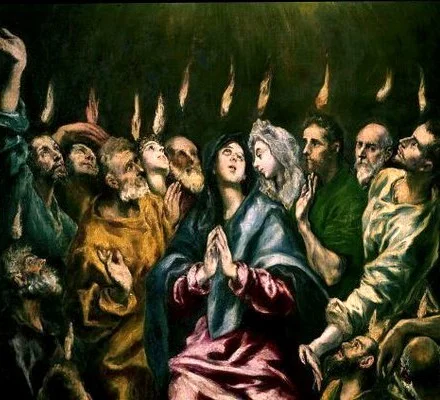

Matthias Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece

Yet, in the course of the 20th Century we see the suffering God becomes a regular theological theme. Dietrich Bonhoeffer writing from his cell in the prison camp reflects ‘only a suffering God can help’. This idea is taken to its extreme in process theology (that theology which places God firmly alongside his creation in suffering). Alfred Whitehead, the famous process thinker pronounced: ‘God is the fellow-sufferer who understands’.

In the context of a century which saw humankind inflict untold pain and suffering on itself, such a conception of God is attractive. God doesn’t abandon us to the pain and mess we’ve got ourselves into, he suffers with us. If left here, this theology is little more than a comfort blanket. It gives us consolation in our suffering that at least God suffers too.

What are we to make of the claim that God suffers?

Bonhoeffer embraces God’s suffering as part of ‘an abandonment of the false conception of God, and a clearing of the decks for the God of the Bible’. Getting rid of false conceptions of God is often the most we can hope theology will achieve. We often find help in this task from the most unlikely of sources. One of the greatest achievements of Richard Dawkins and the New Atheists has been to help put to bed some false conceptions of the god none of us worship.

Is God’s impassibility such a false conception of God? Is the idea of God who is incapable of suffering part of an instinctive false understanding of the Godhead which needs to be put to rest?

On the road to Emmaus, the Risen Jesus says to his two followers: ‘Oh, how foolish you are, and how slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have declared! Was it not necessary that the Messiah should suffer these things and then enter into his glory?’ (Luke 24.25-26).

‘The Messiah should suffer’.

We know that the Cross is at the centre of the Christian faith. We have as one of our central motifs the image of a man undergoing prolonged and excruciating suffering. Theologies get themselves into trouble if the Cross ceases to occupy this central place - but they also get themselves into trouble when the Cross is abstracted from the whole of the life of that man, the life of God himself. The Cross isn’t the arbitrary suffering of one man for all of us. The Cross is the means by which we put to death the human life of the living God himself - and the whole of that human life of God is the basis of all our theology, not just its end.

And it’s not just the end of that life which raises questions for the doctrine of divine impassibility -it’s not just his death which raises questions about whether we can still say that God is incapable of suffering. The whole of his life as one of us forces this question. All of us know, some of us too well, that human beings suffer. They are liable to hurt and change. They grow, age, and feel pain. If God is one of us in Christ, as we know him to be, God in Christ suffers.

We’ve put our fingers on one of those tensions which Christian orthodoxy seems frustratingly happy to let be. The impassible God suffers.

There are a number of paths open to us here, and some have been taken within the course of Christian orthodoxy. We can side-step the tension, and take recourse in the ‘communication of idioms’ (another great phrase!) which means that we can ascribe to God what happens to Christ in his human nature, and to Christ’s humanity that which is proper to him as God. We can say God suffers in Christ, because Christ is fully human, and so fully liable to suffer and change, whilst leaving his divinity impassible. Yet this seems like a trick of the tongue, and raises questions for our theories of salvation too. It runs the danger of reducing the Incarnation to a word-game, and doesn’t let divinity touch the very stuff he came to save.

Bonhoeffer writes further of the impassible God who suffers - the God ‘who conquers power and space in the world by his weakness’. Herein lies our key. We can say God suffers in Christ. It’s obvious from reading the Gospels that Christ suffers, and we know Christ to be God. But we can go further too.

God isn’t just Whitehead’s ‘fellow-sufferer’. He isn’t a passive victim who enters into our pain as a means of solidarity or empathy. He doesn’t suffer with us. God suffers for us. Or rather, God’s relationship to suffering isn’t ours. We’re trapped in the cycles of pain and suffering we experience and all too often cause. God’s suffering doesn’t touch his impassibilty, because God’s suffering is transformative.

In Bonhoeffer’s words he ‘conquers power and space in the world’ not despite his weakness but through it. God’s suffering transforms suffering and means that he, not that suffering, is the last Word.

It’s here we know that the very limits of suffering, death itself, have been destroyed by him in Christ. We know this as witnesses to the Resurrection. God doesn’t suffer suffering. He transforms it. He doesn’t consider impassibility a thing to be gasped, but empties himself taking the form of a slave. And he asks us to do likewise, to transform and put and end to all the suffering we see - except as human beings we’re often more likely to be the cause of suffering than to cure it.

As human beings we cling to power, God sheds it. As human beings we flee suffering, God transforms it. As human beings we cause suffering, God endures it. Christ is his last word on the matter. God suffers with us, but more important, for us - so in that last word we too might be fully alive, and free from the suffering this life brings.