God and Emotions series -- "God's Justice, God's Mercy"

In this fifth and final instalment of our on-going series on God and Emotions, Fr Simon Cuff writes on God's justice and mercy.

We almost all have sung the famous hymn by Fr Frederick Faber: ‘There’s a wideness in God’s mercy’. It’s often sung in such a way that makes God sound like an avuncular sort of chap that you’d be keen to have a pint with, a thoroughly nice bloke who’s kind to everyone, wouldn’t hurt a fly.

All of our images fall short of the reality of the living God. There’s a long theological tradition of negative (or in technical terms: ‘apophatic’) theology which is rightly very suspicious of giving space to any of the images or conceptions of God we can form for ourselves.

The images we have of God in our mind’s eye are often those we’ve picked up from childhood or the world around us. They can be seemingly inane like the image of God as a nice bloke, or they can be harmful, like the image of an angry god which can turn us away from living in relationship with God altogether. Even the seemingly inane nice ‘guy’ image of God can have harmful consequences. This sort of god in our mind’s eye anthropomorphises the divine, makes a god in our own image, and, more perniciously, furthers the lie of the superiority of maleness.

When we come to think about God’s justice and mercy these images are at the forefront of our mind. The angry god and the lovely god battle against each other in our minds’ eye, and depending on our temperament we’re as likely to pick one over the other and we end up with a god who is an exacting judge or a god who turns a blind eye to our misdeeds.

Scripture, and the tradition of Christian orthodoxy, hold God’s justice and mercy together in the kind of creative tension which is often a feature of the grammar of orthodox Christian thought. Passages emphasising God’s mercy sit alongside passages emphasising God’s exacting justice. Passages implying a divisive judgement of humankind sit alongside passages that strongly suggest that God wants all people to be saved. (The Rolling Stones were singing about humankind when they sang, ‘You can’t always get what you want’. Whereas we’re not able to get what we want, Christian orthodoxy generally suggests God is).

Recalling the doctrine of divine simplicity, we remember that whatever God’s justice is, it’s identical to his mercy. God is God, and God is just, and God is merciful. God’s justice is God’s mercy. God’s judgement is God’s mercy. It’s not that he’s kind to some and exacting on others, but that whatever God’s judgement means and whatever God’s mercy means they are from the one and the same pure act of God being God. God is God.

When we get down to asking what does it mean for God to be just? What does it mean for God to be merciful? We struggle. The long tradition philosophical enquiry stemming from at least the time of Socrates shows that we struggle even to understand what it means for justice in human terms, how much more so in God’s. When asking what does it mean for God to be merciful and just, we face as many problems as we do asking what does it mean for God to be God? Until we see him face to face our best approximations of God’s justice and God’s mercy will fall short of the reality of God himself. The God who is simply God…, and just, and merciful.

When considering whether God might be so merciful as to deliver on his will for all to be saved by bringing all to salvation the theologian Karl Barth stops short at proclaiming this as the case. In his Church Dogmatics and elsewhere, he states that neither can we say he will save all of us nor can we say he won’t. Instead, Barth proclaims the freedom of God to decide either way.

When we look again at the words of Faber’s famous hymn, we see that it is as much about mercy and justice, as it is about liberty. ‘There’s a wideness in God’s mercy, like the wideness of the sea; there’s a kindness in his justice, which is more than liberty’. This isn’t the kind of liberty which makes God reckless, free to do as he pleases, but that liberty which we in theological terms we know as Grace. The free gift which God offers us in the Christian life, the free gift which is given to all humankind in Christ.

Faber’s hymn is really a meditation on the extent of this grace: ‘grace enough for thousands of new worlds as great as this; there is room for fresh creations in that upper home of bliss’.

In reflecting on God’s grace, Faber takes us back to the upper room in which humankind was given the pledge of this gift, the institution of the Eucharist, the gift of Christ himself. He reminds us that all theology begins and ends with Christ.

Faber’s hymn was originally published as ‘Come to Jesus’ and includes the words ‘Pining souls come nearer Jesus, and oh come not doubting thus, but with faith that trusts more bravely his huge tenderness for us.’

God’s mercy is God’s justice. God has revealed himself us uniquely in Christ. Christ is God’s mercy and God’s judgement. Here too we encounter freedom. Not the freedom of God to which Barth pointed us, but our freedom in Christ. ‘It was for freedom that Christ set us free’ (Gal 5.1). God’s free gift gives us our free

In Christ, God shows us his mercy and enacts his judgement. In Christ, we find our freedom - the true freedom for which we were created. In Christ, the image of God is restored in us and we are free to live out our share of the Risen life.

This is the Christian life. Not fearing God’s judgement, but living his mercy - rejoicing in our share in the free gift of Christ himself. Faber was confident that if we lived that life today, all would be well: ‘If our love were but more simple, we should take Him at His word; and our lives would be all sunshine in the sweetness of our Lord’.

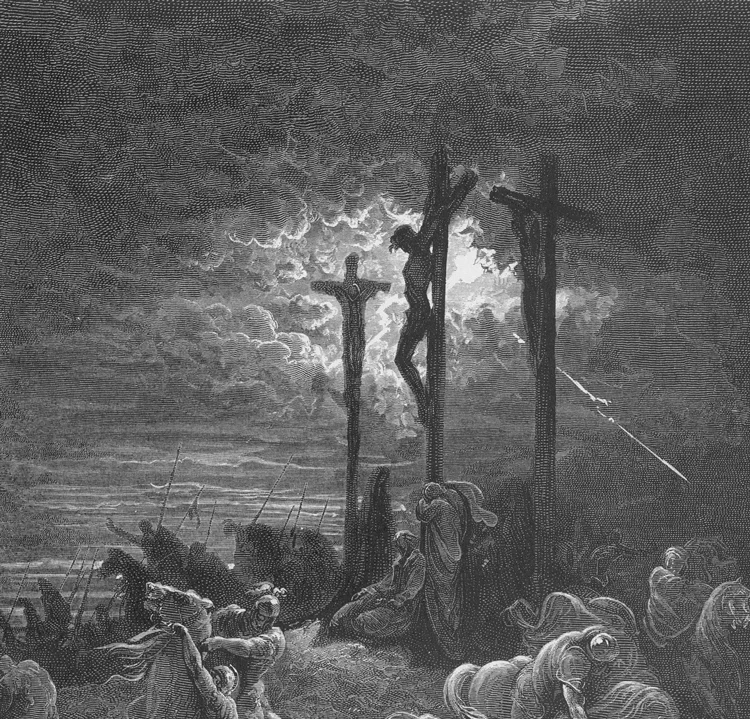

Gustave Doré, The Curcifixion.

Fr Faber was a little optimistic here. We know that the Christian life isn’t all sunshine, even in Christ we’ll have our fare share of knocks and scrapes, we won’t experience an end of suffering in this life. God’s free gift to us doesn’t free us from death, but through it. We get to Easter Sunday through Good Friday.

But Fr Faber was right. Not only is God simple, but so too the whole of the Christian life. If our love were as simple as the God we worship, we’d take him at this word: ‘Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me; for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light.’

By clinging to Christ, by feeding on him in the Sacraments of the Church, we can come to him today, even now, so that by Grace, by his free gift, we dwell ever more in him, and he in us: living his mercy, and opening ourselves to the transforming judgment of the love of God.