Advent: Season of Liberation

Advent, like Lent, can seem difficult to characterise: they are, like Spring and Autumn, often considered transitional seasons. Drawing on the liturgical texts and hymns for this season, Fr Daniel Trott argues that Advent is the season of liberation. Fr Daniel is curate at St John Upper Norwood.

Blessed be the Lord the God of Israel,

who has come to his people and set them free. [1]

1. Introduction: What is Advent about?

Advent suffers from a crisis of identity: is it a period of preparation for Christmas, or a period in which we think about Christ’s second coming ‘to judge the living and the dead’?

Originally, it seems to have been neither. Advent probably began as forty days of fasting before baptisms on the Epiphany (6th January), but Pope Gregory I (r. 590–604) changed it into a four-Sunday season at the end of the Christian year focusing on Christ’s second coming [2]. Later, Advent came to be seen as a preparation for Christmas, and the dual emphasis we are familiar with today, on the birth of Christ and his return in glory, came into being.

But these two themes aren’t really the key to Advent. The second coming of Christ only appears in the gospel readings on the First Sunday of Advent and the birth of Christ is only looked forward to on the Fourth Sunday of Advent. The two Sundays in between focus instead on John the Baptist’s heralding of Jesus and his ministry.

In this essay I want to show that there is a theme that runs through Advent, a theme more central to the gospel than the fear of judgement or the birth of a baby, a theme which can rouse us from our complacency and bring Advent back to life. Obvious as it may sound, Advent is about the coming of the Messiah and his kingdom, and this kingdom is a kingdom of liberation.

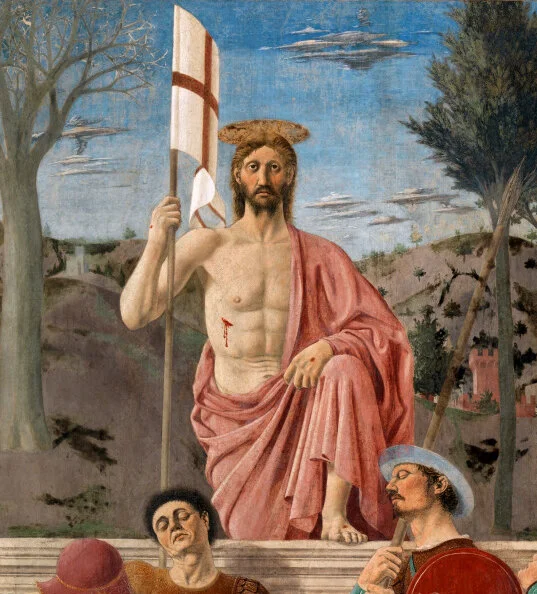

Christ Opening the Gates of Dachau. Altarpiece at the Resurrection of Our Lord chapel, Dachau.

2. The Advent readings

The Sunday Principal Service readings [3] in Advent show very clearly that it is the coming of the Messiah for which we are preparing. This is most obvious on the Second and Third Sundays of Advent, when the gospel readings narrate John the Baptist’s heralding of Jesus. John the Baptist is not, of course, heralding Jesus’s birth, but his ministry, and it is this ministry in which Jesus’s messianic status is most apparent. In his ministry Jesus proclaims and inaugurates the ‘kingdom of God’, the utopian future when humanity and the whole of creation becomes what God desires it to be. In one of the gospel readings the signs of this kingdom are mentioned:

the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have good news brought to them.

(Matt. 11.5)

The other gospel readings on the Second and Third Sundays of Advent do not make it clear what the coming of the Messiah means, but the Old Testament readings fill this gap. The coming of the Messiah means righteousness for the poor and universal peace (Isaiah 11.1–10), the strengthening of the fearful (Isaiah 35.1–10), liberty to the captives and comfort to those who mourn (Isaiah 61.1–4,8–11), and God’s protective presence in our midst (Zephaniah 3.14–20).

It is worth bearing this in mind on the First Sunday of Advent, when the gospel readings are all taken from the apocalyptic sections of the synoptic gospels (Matt. 24.36–44; Mark 13.24–37; Luke 21.25–36), and emphasize the need to ‘keep awake’ and be ready for ‘the coming of the Son of Man’. The overall impression these readings give is one of fear, and over the centuries the church has done much to encourage this fear: medieval doom paintings, fire and brimstone preaching, and threats of the retention of sins. But within one of the readings itself there is hope:

Now when these things begin to take place, stand up and raise your heads, because your redemption is drawing near.

(Luke 21.28)

And most of the other readings appointed for this Sunday continue this theme of hope. We are reminded that the Messiah’s future kingdom will be peaceful (Isaiah 2.1–5) and just (Jeremiah 33.14–16), that Christ’s coming spells salvation (Romans 13.11–14), that God’s judgement is a positive thing for his people (Isaiah 64.1–9), and that God will strengthen us to the end (1 Corinthians 1.3–9). The readings on the First Sunday of Advent are not supposed to be fearful, but are supposed to make us look forward to the consummation of all things, when God’s kingdom will come.

So what about the Fourth Sunday of Advent? Here we narrow down on Christ’s birth: the gospel readings all narrate events preceding this, and the Old Testament and New Testament readings circle around the same theme. Even here, though, in Years B and C the canticle (appointed in preference to a psalm) is the Magnificat (The Song of Mary), which looks to the great reversals of God’s kingdom:

He has shown strength with his arm

and has scattered the proud in their conceit,Casting down the mighty from their thrones

and lifting up the lowly.He has filled the hungry with good things

and sent the rich away empty.

Thus even when Christ’s birth is in view, we are really looking forward to his inaugurating of the kingdom in his ministry, and the final consummation of that kingdom on the last day, when people will be liberated from poverty, hunger, and the powers that oppress them.

In Gustavo Gutiérrez’s concept of ‘integral liberation’, liberation has three interrelated levels: socio-economic/political, human/psychological, and religious/theological.[4] The texts about the Messiah’s kingdom that we have looked at focus on the first two levels (freedom from violence, fear, captivity, sorrow), but discussion of salvation has often been dominated by the third level: ‘you are to name him Jesus, for he will save his people from their sins’ (Matt. 1.21). The readings appointed in Advent invite us to understand salvation in a wider sense, and to hope for and seek the liberation of all God’s creation in the broadest possible terms.

3. Other Advent liturgy

The theme of the liberation promised by the Messiah’s kingdom is picked up in other places in the Advent liturgy, particularly in hymns. In earlier hymns, the language of ‘freedom’ is more likely to be applied to the theological or psychological levels, e.g. in Charles Wesley’s Come, thou long-expected Jesus (1744) it is from ‘our sins and fears’ that Jesus will ‘release us’:

Come, thou long-expected Jesus,

Born to set thy people free,

From our sins and fears release us,

Let us find our rest in thee.

Philip Doddridge’s Hark the glad sound! (1735) is similarly psychological (‘the broken heart’, ‘the bleeding soul’) and theological (‘the treasures of his grace’) in the liberation it heralds:

He comes the prisoners to release

In Satan’s bondage held;

The gates of brass before him burst,

The iron fetters yield.He comes the broken heart to bind,

The bleeding soul to cure,

And with the treasures of his grace

Enrich the humble poor.

Although these hymns see Advent as promising liberation, the way in which that liberation is understood is fairly restricted.

In more modern hymns the concept of liberation is often broader. Martin Leckebusch’s People, look east (2000) makes reference to ‘justice’ and ‘lives restored’:

God reaffirms the gracious call:

words of welcome meant for all;

comfort enough for all our sorrows;

justice shaping new tomorrows.

Mercy bears fruit in lives restored,

freed to praise and serve the Lord.

Bernadette Farrell’s hymn Christ, be our light! (1993) is a sustained exploration of the theme, including these verses:

Longing for food, many are hungry.

Longing for water, many still thirst.

Make us your bread, broken for others,

shared until all are fed.Longing for shelter, many are homeless.

Longing for warmth, many are cold.

Make us your building, sheltering others,

walls made of living stone.

Thus Advent is celebrated as a time to hope for, pray for, and work for the kingdom of God and the liberation of all.

One of the ways in which the theme of liberation finds particular expression in Advent is by recollection of the Old Testament hope of Israel’s return from exile. Several of the Principal Service readings make reference to the return of Israel from exile (Isaiah 40.1–11; Baruch 5.1–9; Isaiah 35.1–10; Zephaniah 3.14–20), inviting us to see Advent through the lens of this hope for freedom. The Advent prose, sometimes used at the eucharist, is also firmly rooted in the exile, being made up almost entirely of texts quoted or adapted from Isaiah 40–64 (the consistently exilic or post-exilic portion of the book).

This connection with the return from exile is even more prominent at Morning and Evening Prayer. Chapter 40 of Isaiah (‘Comfort, O comfort my people, says your God’) is always begun on the Monday after Christ the King (a week before Advent), and the book is more or less read through until the Saturday after 6th January, keeping the return from exile in mind right up until the lectionary begins to look at Jesus’s adult ministry on the feast of the Baptism of Christ. Canticles also keep the exile in view. The canticle that follows the psalms at Morning Prayer is ‘A Song of the Wilderness’ (Isaiah 35.1,2b–4a,4c–6,10), and the alternative canticles are ‘A Song of God’s Herald’ (Isaiah 40.9–11) and ‘A Song of Baruch’ (Baruch 5.5,6c,7–9) – all strongly exilic texts.

The exile also appears in one of the most well-known Advent hymns, O come, O come, Emmanuel! (1710) although there is no reference to the exile in the Advent antiphons on which it is based:

O come, O come, Emmanuel!

Redeem thy captive Israel,

That into exile drear is gone

far from the face of God’s dear Son.

Thus the exile serves as something of an interpretative lens for the coming of the Messiah, though to nowhere near the same extent as the exodus does for Easter. Although Easter remains the primary Christian feast of liberation, and draws much of its imagery from the primary Jewish story of liberation, Christmas too should be seen in these terms, and Israel’s return from exile provides a lens through which to interpret it.

4. Conclusion

So Advent is about the coming of the Messiah to usher in his kingdom of justice, peace, and liberation. It is not a time to quake in fear at the prospect of Jesus returning in glory, nor is it a time to concentrate on the birth of baby Jesus. It is instead a time to reawaken our hope for God’s future. It is a time to pray fervently

your kingdom come,

your will be done,

on earth as in heaven. [5]

It is a time to ask

Lord of all life,

help us to work together for that day

when your kingdom comes

and justice and mercy will be seen in all the earth. [6]

It is not a time to wait, it is a time to hope – to hope actively against all the powers of evil [7], to pray and to work for the kingdom of God.