Hymns and Carols: Creator of the Stars of Night

We are pleased to depart from our regular schedule to squeeze in one more post before Christmas, on the Advent office hymn, Creator of the Stars of Night. Dr Jeremy Llewellyn teaches historical musicology at the University of Vienna. Watch out for this forthcoming book on Textlessness in Medieval Music 800-1300.

The series on hymns and carols will continue into Christmastide.

A hymnic guide to watching

Watching is so difficult. It can feel incredibly self-conscious, awkward, indulgent, or even just plain boring. Yet watching is what we are called to do in Advent as we await the coming of the Lord in our midst. ‘When these things begin to take place, stand up and lift up your heads, because your redemption is drawing near,’ (Luke 21.28) is the gospel injunction, as greeting the apocalypse should be done fearlessly in faith. For some, this merely exacerbates the awkwardness of watching since, apparently, it is now necessary to adopt a power stance – legs spread widely, head cocked on high.

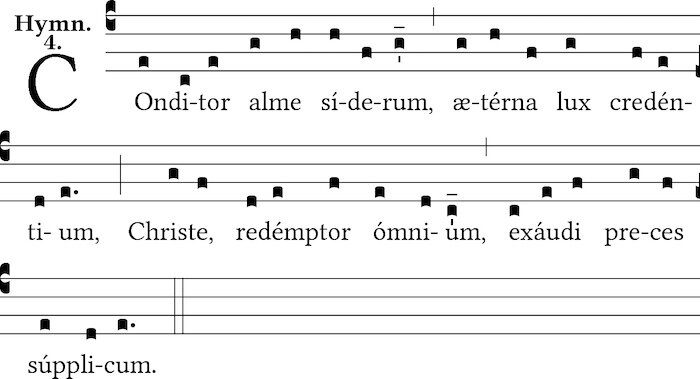

The beauty of the hymn Creator of the Stars of Night is that it seems to provide a spiritual instruction manual for watching. It achieves this through its content but also through its form, both poetic and, arguably, musical. As such, it can function as a meditative aid as Advent draws towards its darkest and most silent point. The poet of the original Latin text, Conditor alme siderum, is unknown but it appears as if the hymn formed part of the so-called ‘New Hymnal’ which began to be assembled in the ninth century. [1] The Carolingians were supremely interested in codifying texts of all sorts and learning flourished, most especially in the monastic centres led by Benedictines. The cloistered life – however industrious or economically successful – lent itself to a mindset of reworking textual traditions, often through ritual. It was exegesis through praxis. Thus it should come as no surprise that the hymn Conditor alme siderum was based on older models.

From Bréviaire de Paris.

‘Ambrosian’ in name, the particular form of a strophe consisting of four lines each with eight syllables was linked to the name of the fourth-century archbishop of Milan. In fact, the subject matter of Conditor alme siderum, especially the later strophe which focuses on the Virgin Mary, seems very close to an earlier hymn found in the ‘Old Hymnal’, Veni redemptor gentium. Re-using older models should not, however, be regarded in terms of a lack of inventiveness or creativity. Hymns played an important role not only within the liturgy of medieval Benedictine establishments, but also in the schoolrooms. When it came to supplying examples of poetry in his teaching of grammar, Bede (672/3-735) dispensed with authors from Classical Antiquity and instead inserted lines from hymns in his De arte grammatica. A hymn like Conditor alme siderum would have fitted into Bede’s classification of the verse form known as the ‘iambic dimeter’ with its alternation of short and long syllables (although there is considerable variation in the pattern throughout the European Middle Ages). J. M. Neale (1818-1866), the great Anglican translator of hymns, was certainly aware of the poetic tradition of the hymns he artfully rendered in English and Conditor alme siderum – now Creator of the Stars of Night – is no exception. Furthermore, it is possible to see his process of translation from the medieval Latin as coloured by theological reflection, very much in the Benedictine spirit of building on tradition.

Where do you start with a meditation on watching? Obviously, with the most elemental of ocular explorations: star-gazing.

Creator of the stars of night,

Thy people’s everlasting light,

Jesu, Redeemer, save us all,

And hear Thy servants when they call.

Stars have not have a bad 2019 with the 50th anniversary of the Moon Landing, the release of the final epic film in the Star Wars series alongside the various apps available which allow you, by pointing your smartphone at the heavens, to identify constellations. Obviously, the elemental fascination with the starry firmament persists, however large the leaps of astronauts or commercial technology. Theologically, the anonymous hymn-writer links the astral expanse with the work of the Creator (Genesis 1.16) before taking up the idea of ‘light’ which is presented most powerfully in the Christmas season in the prologue to John’s Gospel: ‘the light shines in the darkness and the darkness has not overcome it,’ (John 1.5). Indeed, the very next line of the hymn text names Jesus in the vocative and it becomes clear at this point in the strophe that Jesus is also the ‘creator of the stars of night’ as this, too, is placed in the vocative in the original Latin. Again, the Johannine resonance is striking as ‘through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made,’ (John 1.3). This includes the stars. The Latin continues that Jesus is ‘redemptor omnium’ – the ‘Redeemer of all’ – which Neale swerves in his translation by anticipating the invocation of the final line of the strophe (‘hear Thy servants’) at the end of the penultimate line (‘save us all’).

Watching the stars thus becomes a means of meditating on the Incarnation. In his anguished pleas for justice, Isaiah had already encouraged the faithful to look to the heavens and ask who brought forth the heavenly bodies, naming each one of them (Isaiah 40.26). In fact, the mapping of the star-filled firmament onto earthly preoccupations is a recurrent theme in the Old Testament. Most obviously, this concerns Abram who is promised by God that his descendants will be as numerous as the stars in the sky, if he can count them (Genesis 15.5). In addition, the language of the Psalms has God counting the stars and calling them by their name (Psalm 147.4) and even, as the omnipotent Creator of the ‘moon and the stars’, being mindful of humanity (Psalm 8.3).

The mapping that takes place in Creator of the Stars of Night is redemptive. The smallness and insignificance we feel in the face of the innumerable constellations in the heavens becomes a sign of the boundless nature of Christ’s redemptive purposes. We do not have to go as far as St Jerome (c 347-420) who comments on the Isaiah passage by describing humans as, ultimately, a ‘species of grasshoppers’ when compared to the power of the Creator. Nor do we have to score the bounds of God’s redemption geographically, as Jerome did, from ‘the Indian sea to Britain, and from the Atlantic to the North Pole.’ Watching the stars for the hymn-writer of Creator of the Stars and Night is, therefore, a three-stage meditative process. First, we marvel at the immensity of the starry firmament, brought into creation through the Word. Second, we see the light and recognise darkness cannot overcome it. Third and finally, we realise that creation and light lead to redemption; a redemption that cannot be counted, that cannot be weighed up and quantified, that reaches all. Therefore as supplicants, whom God in His mindfulness individually counts and names, we are able to offer in return our prayers.

The rest of Creator of the Stars of Night fills in the back story to this creative, light-filled act of redemption. It uses thereby a number of Advent themes. In strophe two, the weariness of the world comes to the fore as the Latin original speaks of the ‘mundus languidus’, the ‘listless world’. This, too, taps into the prophecy of Isaiah of a people weary and weak (Isaiah 40.28-31). Yet Neale seizes his chance to do something more adventurous with the translation of this passage. The chronological priority of his choices is difficult to reconstruct at this remove, but it is highly tempting to see his use of the word ‘universe’ (‘Thou, grieving that the ancient curse/ Should doom to death a universe’) as a response to the glittering stars of night. This leaves the problem of finding a rhyme-word for the previous line and ‘curse’ fits the bill perfectly. Thus Neale is able to take the Latin reference to the ‘age perishing by the devastation of death’ (‘interitu/mortis perire saeculum’) and wrap it into a Scriptural understanding of Adam’s sinfulness being banished by Christ’s coming (Romans 5.12-14). Medicine is then offered the languid ‘sinners’ or, in the Latin original, ‘reis’ which Neale, interestingly, renders vocally – not semantically – as ‘race’ (‘Hast found the medicine, full of grace/To save and heal a ruined race’).

The image of decline continues into strophe three of the hymn ‘as drew the world to evening-tide’. This is the moment for Christ to issue forth. Again, a thickening of Biblical allusion, so beloved of the Benedictines, seems to take place. On the one hand, the ending of one age and the beginning of another opens the Epistle to the Hebrews (Hebrews 1.1-3) and, on the other, an evening-tide watchfulness informs the Parable of the Ten Virgins with their lamps, expectantly awaiting the Bridegroom (Matthew 25.1-13). Both mark out time and are pregnant with expectancy. Of course, the references to ‘evening’ in both the Latin original (‘vespere’) and Neale’s translation gain added poignancy by the liturgical assignation of the hymn as the Office hymn for evening services in Advent. In strophe four, the hymn-writer moves away from the eschatological and yet still wishes to find a Scriptural reference to starriness. His solution, followed by Neale, is to reach for Philippians 2.10-11 where ‘at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth’ – ‘caelestia, terrestria’. A reference to the judge of future ages forms the centrepiece of strophe five before the hymn comes to an end in strophe six with a typical doxological formulation giving glory to God the Son together with the Father and the Holy Spirit ‘from age to age eternally’.

From Liber Hymnarius, Solesmes, 1983, p. 3

Turning to the music of Creator of the Stars of Night, it seems - to me, at least - that the plainsong melody as given in the standard hymnals captures the essence of the text. It is incredibly simple with only one note per syllable, unlike other plainsong office hymns which often inexplicably bunch groups of notes to one syllable but not the next, creating a sense in the singer of navigating a melodic minefield. The range of the melody sits easily - not too low and not too high - but there is a gentle swoop at the beginning as the stars on high are contemplated. The melody appears modest and serious, which are precisely the terms used by the medieval theorist, Frutolf of Michelsberg (d 1103) to describe melodies of this type (in mode IV or the plagal deuterus, in technical terms). Watching the stars melodically is a matter of modesty. But, at the same time, it is a chance to acknowledge the glory of God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit - at least for Anglicans (and more traditional Anglicans at that). This is because the plainsong melody used by Marbeck for the Gloria is also in mode IV. As an experiment, you can sing the melody of Creator of the Stars and Night and then immediately slide into the Gloria. Or else sing along to recordings on YouTube (see below). The melodies sit very well together, often using the same palette of notes and gestures. This is another intimation - sonic, this time - of the Benedictine habit of working and reworking tradition.

One final point can be made about the form of Creator of the Stars of Night and its Latin original which is relevant for meditative practices around watching. In terms of poetic form, there is not much you can do with a line of eight syllables alternating short and long. In this case, however, the hymn-writer took up the challenge to fill those lines with epithets about God. Thus, translating from the Latin, God is called ‘blessed creator of the stars’, ‘eternal light of believers’, ‘redeemer of all’ (strophe one); ‘bridegroom from the bridal chamber’ (strophe three); ‘judge of future generations’ (strophe five); and ‘most holy king’ (strophe six). Such epithets can illuminate our prayers and intercessions during Advent. And when words fail, there always is the possibility of just looking up at the stars. Perhaps watching is not so difficult after all.

Notes

Creator of the stars of night,

Thy people’s everlasting light,

Jesu, Redeemer, save us all,

And hear Thy servants when they call.

Thou, grieving that the ancient curse

Should doom to death a universe,

Hast found the medicine, full of grace,

To save and heal a ruined race.

Thou cam’st, the Bridegroom of the bride,

As drew the world to evening-tide;

Proceeding from a virgin shrine,

The spotless victim all divine.

At whose dread name, majestic now,

All knees must bend, all hearts must bow;

And things celestial Thee shall own,

And things terrestrial, Lord alone.

O Thou whose coming is with dread

To judge and doom the quick and dead,

Preserve us, while we dwell below,

From every insult of the foe.

To God the Father, God the Son,

And God the Spirit, Three in One,

Laud, honor, might, and glory be

From age to age eternally.