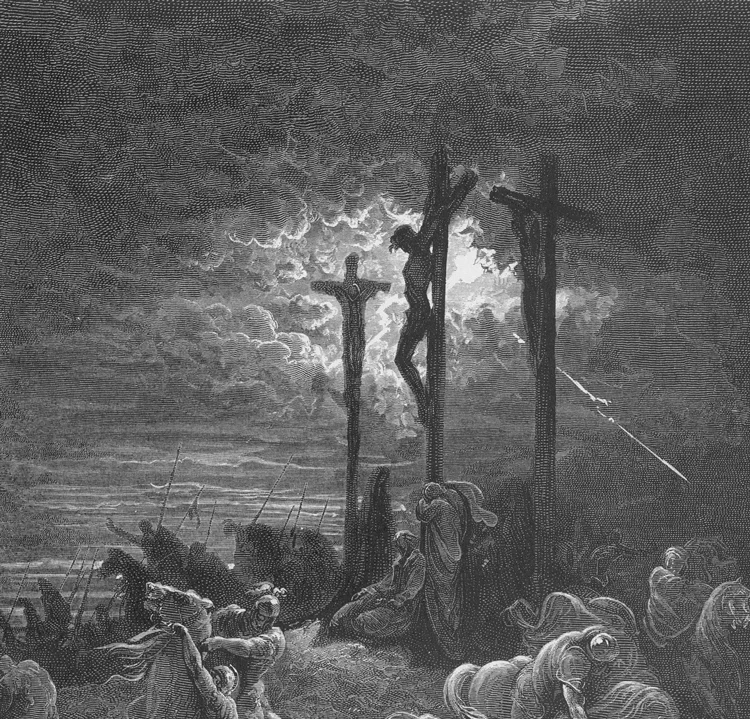

God and Emotions series -- "The Wrath of God"

Fr Simon Cuff begins our series on God and Emotions with an essay on the wrath and anger of God. God and Emotions is an on-going series, with a new essay very month or so, and will include articles on divine love, justice and mercy, jealousy, and suffering. New essays in this series will appear monthly.

The phrase the ‘wrath of God’ fills us with dread. And quite rightly. For many the wrath of God is so terrifying that the idea of living any sort of Christian life at all is as terrifying as the wrath they fear. If nothing else, it’s important to remember from the outset that anger of God is identical with the love of God. If we fear God’s wrath, we can remember that it is nothing less than God’s love. And there’s not a single thing we can do that will make God love us any less than he does already, since he created us and called us into being.

If Christians today think about God’s anger at all, we tend to associate it most obviously with theories of salvation - theories about how God’s anger comes to cease, thanks to his own actions in Christ upon the cross. Some Christians find the idea of God’s being angry at all difficult. I don’t want to add fuel to these debates, but to make a more fundamental point about the nature of God. What both those Christians who stress God’s anger and those Christians who stress God’s love tend to forget is that whatever God’s anger is, it is identical with his love. God’s anger is God’s love.

In doctrinal terms this stems from ‘the doctrine of divine simplicity’. The philosophical theologian Nicholas Wolterstorff notes the extraordinary prominence medieval theologians - Jewish, Christian, and Muslim alike - gave to the doctrine of divine simplicity. This is the belief that God is simple, in him there are no distinctions whatsoever. All of God’s properties: his justice, his mercy, his anger, his love are identical. God is simply God. God is God. God is simple.

Wolterstorff goes on to note the fecundity of this doctrine for theology: ‘If one grants God's simplicity, then one also has to grant a large number of other divine attributes: immateriality, eternity, immutability… If one grants that God is simple, one's interpretation of all God's other attributes will have to be formed in the light of that conviction’ [1].

If one grants that God is simple, then God’s anger is God’s love. Unlike human anger or human love which differ because they are different properties or states within the loving woman or angry man, divine anger is identical to divine love and differs in how it impacts upon its object. The same God’s action in the world is perceived as love by some and anger by others, depending on their standing in relation to that action. God’s grace is simply God.

The Harrowing of Hell. Chora Church, Istanbul.

In some understandings of judgement day, God doesn’t burn some whilst welcoming others to heaven, God simply acts so that he is all-in-all; what is outside of Christ doesn’t survive the fire of God’s love; only what is in Christ will remain, all within the one-and-the-same action of God.

Our problem is that we’re not very good at working out what God loves and what makes God angry - as the spiritual quoted by Rowan Williams at the end of his Christian Theology reminds us: ‘Nobody knows who I am ‘till judgement morning’ [2]. Until we see God face to face, we won’t be sure that we’ve correctly identified the object and extent of God’s love and of his anger. God knows, and that’s enough.

God is simple. God’s love is God’s anger. Divine anger differs from human anger.

Human anger affects the person who is angry - raised pulse, red face, high blood pressure. Divine anger transforms the object of God’s anger. Deena Grant has shown that in the Hebrew Bible, our Old Testament, the Hebrew word for ‘anger’ when applied to humans describes a state in that person [3]. When applied to God, the word describes the trajectory of anger toward a target. This is clearest when she looks at the relationship between ‘anger’ and ‘burning’. Human anger burns up the angry person. God’s anger burns towards the object of his anger.

Our anger changes us, it raises our blood pressure. God’s anger changes what he’s angry at - God’s anger transforms.

We know that if we want to see God most clearly in this life, we look to Christ. We know too - how many times have many of us preached - that it’s okay to be righteously indignant, because Jesus was righteously indignant in the Temple (Matt 21.12-13; Mark 11.15-17; Luke 19.45-46; John 2.14-17).

We see Jesus turning the tables on the money-sellers and we teach others that there are some things we can be righteously indignant about. But we shy away from saying it’s ok to be angry, because Christ could never be angry.

We let the image of Jesus we have in our mind from our childhood - the white-skinned, blue-eyed, blonde-haired holier-than-thou lovely-to-everyone Jesus - drive our reading of Scripture. This Jesus doesn’t get angry, because lovely Jesus could never get angry. He gets righteously indignant.

But the Jesus we meet on the pages of Scripture ever-challenges the Jesus we have in our mind’s eye; Jesus ever-challenges the images and idols we make of him. The Jesus of Matthew who chides the Scribes and the Pharisees in Matthew 23 does so passionately, and, we might say, angrily. He doesn’t challenge them inanely, or even nice-ly. I can’t remember who said it but: ‘Nice doesn’t build the Kingdom’.

The best example of our image of Jesus driving our reading of Scripture, rather than our image of Jesus being challenged by it, is in the raising of Lazarus in John 11. This is one of my favourite episodes in Scripture, a passage that’s vital in our theologies of healing and in speaking into our society’s aversion to death.

It doesn’t start well. You can almost sense Jesus’ frustration with the disciples.‘Our friend Lazarus has fallen asleep, but I am going there to awaken him.’ The disciples said to him, ‘Lord, if he has fallen asleep, he will be all right.’… Then Jesus told them plainly, ‘Lazarus is dead.’

Then, Jesus arrives at Bethany and Mary and Martha are grieving. He sees Mary crying tears of grief, and the Jews with her weeping. And he was greatly disturbed in spirit and deeply moved. He weeps. He arrives at the tomb and is again greatly disturbed. Jesus is sad at the death of his friend. Lovely Jesus.

Except when we look at the Greek, our image of Jesus is challenged. What’s translated here as ‘greatly disturbed in spirit’ and ‘deeply moved’ are more usually rendered ‘snorting with anger’ and ‘deeply agitated’. We let our image of Jesus drive our translation. We can’t bring ourselves to say ‘Jesus is angry’. We water this down: Jesus is ‘greatly disturbed in spirit’. We don’t let our view of what it means to be good be challenged by the Jesus that actually meets us in Scripture. And what happens when Jesus gets angry? Stuff happens. Jesus’ anger transforms the situation. Lazarus is raised and through this many believe - in Jesus, and that death, though inevitable, is not the end.

All this shouldn’t surprise us. We believe Jesus is the Incarnate God. If we believe in a God whose anger is identical to his love, then we shouldn’t be surprised when we see Jesus exhibiting a kind of anger and when that anger looks a lot like divine anger - that anger which transforms not the person who is angry, but the object of his anger. Jesus’ anger transforms the death of Lazarus, bringing him back to life and many to believe.

There’s one more thing that takes our attention in this passage. Jesus weeps. If Jesus’ tears are like the Jews’, they’re both sad at the death of their friend. But the whole point of this passage is that the Jews’ tears are a sign that they don’t understand what the life of Jesus means for the death of us all. Jesus’ tears occur between two references to his anger. Jesus’ tears aren’t divorced from his anger, they are bound up with it. Jesus is crying as much at the disbelief of his friends as at the death of one of them. Jesus cries with and because of that which makes him angry. His grief is tied up with his anger.

Grief and anger are intimately bound. Our word ‘anger’ comes from the Old Norse word for grief. John Shore responds to a Christian woman who has written to him because she is struggling with the feelings of anger that she has at a mother, about to switch off her son’s life support. He writes: ‘The root of our word anger is, in fact, the Old Norse word angr, which means anguish, distress, grief, sorrow, affliction. And I wasn’t surprised to discover that’s so, because in its purest, most concentrated form — which is to say when it’s attended by perfect helplessness — that’s what anger is: anguish' [4].

If nothing else, our anger is our sadness that the world in which we live is not the world as it might be, that the world in which we live is not the world which God ultimately intends it to be. We can and should get angry at those things which grieve us in the world, that make us sad that they are not as they might be.

Our anger should model itself on God’s anger, which is identical to his love. Our anger should not stop at making us angry but, like God’s anger, should transform the object of our anger. Like God’s anger, all those things which grieve us, which upset us, which make us angry that the world is not in accord with God’s will, should inspire us to make our wrath a little more like God’s, a little more like God’s wrath, like God’s love, which transforms that with which he is angry - that which he loves.

Wolterstorff, N. 'Divine Simplicity’ in Philosophical Perspectives, Vol. 5, Philosophy of Religion (1991), pp. 531-552

Williams, R. ‘Nobody Knows Who I Am ‘Till Judgement Morning’ in On Christian Theology (Oxford: Blackwell 2000)

Grant, D., ‘Brief Discussion of the Difference between Human and Divine חםה’ in Biblica, Vol. 91, No. 3 (2010), pp. 418-424

Shore, J., ‘She’s Pulled The Plug On Her Own Son, Whom I Love. Help?’, available at: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/john-shore/she-pulled-the-plug-on-her-own-son_b_1389652.html