God and Emotions series -- "God is Love"

In this second instalment of our on-going series on God and Emotions, Fr Simon Cuff writes on God's love. Essays on this theme will be published monthly.

Tina Turner famously sang: ’What’s love got to do, got to do with it? What’s love but a second hand emotion?’. In short, the Christian answer to her question is: ‘Everything’.

In God’s case, we can go a little deeper. God is God’s love. God’s love isn’t a second-hand emotion, but God himself. God’s ‘emotions’ aren’t second-hand properties but identical to him and to each other. Recalling the doctrine of divine simplicity, God simply is. God is God. And God is love: ‘God is love, and those who abide in love abide in God, and God abides in them.’ (1 John 4.16).

All well and good. But what does it mean to say ‘God is love’?

As human beings, we are always ready to make god in our own image. We mistake God’s love for an image of human love, and we shape God’s love in our image. As Christians, we know that our vocation is instead to be shaped into God’s image - to reclaim that image given to us in creation and that likeness renewed in baptism. We know that our images of God are to shaped by him, not made by us.

But all too often we end up making God’s love sound like our understanding of love. Except, as human beings, we’re pretty useless at loving. We can make the mistake of thinking we know what love is - complete with the hearts and flowers and cards that the world around us tells us love is - and we make God into a kind of romantic superhero. God’s love is a kind of fluffy niceness that keeps us warm. Or we project our experience of love onto God. The failings of those who were supposed to teach us what it means to love get projected onto God, and we find it difficult to believe that he loves us at all, let alone work out what God’s love might mean.

It’s rather easier to say what love is not. As anyone who has been to a wedding recently will likely have heard, St Paul finds it easier to say what love isn’t, than what love is: ‘Love is not envious or boastful or arrogant or rude. It does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable or resentful; it does not rejoice in wrongdoing, but rejoices in the truth’ (1 Cor 13.4-7)

If we want to know anything about God, our starting point is Christ. If we want to know what love is, we look to Christ. A little earlier in 1 John the author reminds us that in Christ God showed us what it means for him to be love: ‘God’s love was revealed among us in this way: God sent his only Son into the world so that we might live through him.’ (1 John 4.9).

Christ stands as the ultimate refuter of our images of what God might be like. If we fall foul of the temptation to make God in our own image, Christ ever-stands against it. No more is this the case than when we come to think of God’s love.

Christ, God as one of us, reveals to us God’s love. In do so, we see why love is the heart of the Christian faith. In God’s love, central tenets of the faith all come together: Incarnation, Trinity, Sacrament.

‘God sent his only Son into the world so that we might live through him’. God’s love isn’t something that happens at a distance. God’s love for us means that he sends his only Son, God’s love for us means he became one us and took humanity to himself. God’s love is not static or self-interested. It doesn’t cling to itself. Nor is it earned. We’re not loved by God because we love God. We love God because we are loved by him, and in creating us, and becoming one of us, he made us and he made us able to love. In Christ, he showed us what it is to love. We love because he is loves.

‘God sent his only Son into the world so that we might live through him’. God’s love is totally unnecessary. And because it’s unnecessary, it’s entirely gift. That’s what we mean by Grace. God doesn’t need us to be love. God’s love is perfect in itself. We know this from the doctrine of the Trinity - Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. God doesn’t create us as a playmate or because he was lonely. He exists as perfect love. Father poured out to Son poured out to Spirit and vice versa. Perfect self-emptying love.

‘God sent his only Son into the world so that we might live through him’. God’s love for us is complete in Christ, but it doesn’t end in the year 33. The Resurrection teaches us God’s love never ends. Not even death can get in its way. God may have revealed to us his love completely in Christ, but he doesn’t ever stop this self-emptying. He pours himself out in Christ, in the presence of his Spirit in the Church, and no more so than in the Sacraments of his Church. The Sacraments are the best means we have of receiving God’s gift of himself, ever-poured out. The Sacramental life - the regular, lively, and life-giving celebration and reception of the Sacraments - is a life soaked in God’s gift of himself - a life founded on God’s love.

Conception Abbey. Sacred Heart of Jesus.

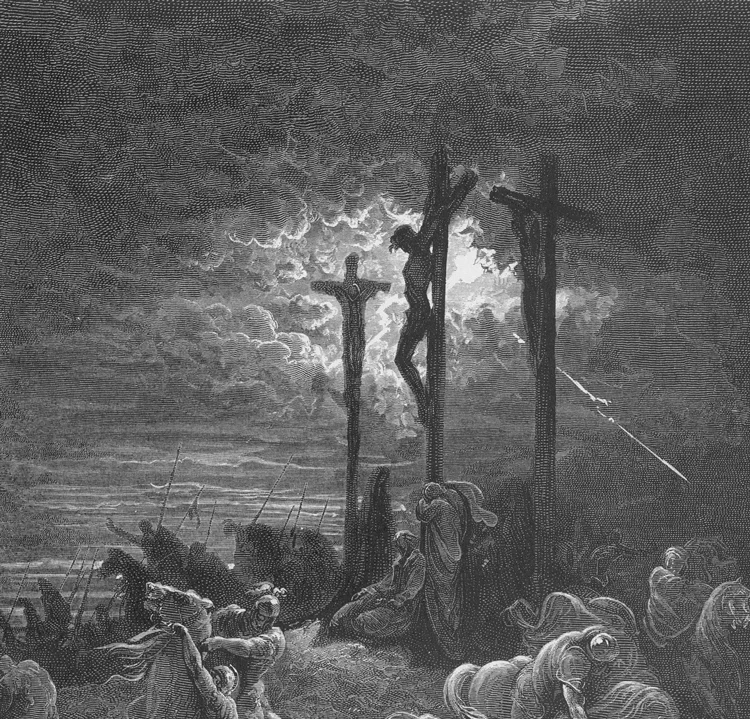

If we want to know what God’s love is like, we look to Christ’s life - the whole of that life. But the best image we have of God’s love is how that life seemed, at first, to come to an end. The Cross shows us what it means to love. Or, rather, it makes explicit the extent of God’s love for us, the lengths he will go to for us and the consequences of what it means to love. In Christ we see God’s love poured out at each and every moment, not just in his death, but in the whole of his life. It his death which stands as the ultimate sign of where loving will take you. The Dominican theologian, Herbert McCabe, describes this best: ‘If you love enough you will be killed. Humankind inevitably rejects the only solution to its problem, the solution of love. Human history rejects its own meaning. Humankind is doomed.’

God’s love is the perfect and eternal gift of self-giving, self-emptying. This self-emptying turns out to be what God’s love is after all, what love is after all. Now we see why it’s easier to say what love is not than what love is. Love is a kind of self-negation.

The perfect image of love we encounter on the Cross doesn’t call us to a morbid emulation - we’re not called to seek out pain and misery in order to repeat the crucifixion. Instead, we’re called to lay aside the false self we’ve created for our selves and all those images and idols to which we cling to. Here in this self-negation, we encounter the mystery of God, because as we lay aside that self, as we pour that self out, as we love, we find that we are actually more really ourselves than we at the outset. We lose our selves only to find ourself, we lay aside our life only to take up the life which God is offering to us even today. We pour ourselves out and find ourselves swept up in that eternal self-offering which is life of God himself, God’s love.

McCabe is right. Humankind is doomed. But we know God loves us, and we know God is love. Humankind is loved, and humankind is called to love - a little less like the images of love we make for ourselves, and a little more like the image of that God in which all of us have been made.