An Appreciation of Robert Alter’s The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary

In 2018, Robert Alter—professor of Hebrew and comparative literature at the University of California, Berkeley—published his full translation and commentary of the Hebrew Bible, the culmination of a career dedicated to reading the Bible. The Revd Dr James Harding (University of Otago) pays tribute to the man as well as the work, and thinks through how we might now read the Bible faithfully. His book on the reception history of the David and Jonathan story was published by Routledge in 2016.

During the summer of 2002, I spent a few weeks in Toronto at the end of a somewhat stressful year teaching Old Testament at a theological college in the Caribbean. I had defended my doctoral thesis a few months earlier, on a subject only tangentially related to the classes I was teaching, and was still very much in that difficult period, only too familiar to most academics, of trying to stay far enough ahead of my students to be able to teach with even a modicum of authority. The combination of post-thesis blues (also familiar to many academics) and the stress of preparing classes on unfamiliar topics in an environment far from home had begun to take its toll, and I was not at all sure that I any longer had either the interest or the enthusiasm to keep me going in a teaching career I had begun more by accident than by design.

Browsing a bookstall one day that sweltering summer in Toronto, I came across a slender paperback by Robert Alter entitled The Art of Biblical Narrative. I had vaguely heard of Alter’s work, and had a faint sense of having heard of the book, though I had never read it (it was first published in 1981, with a second edition appearing in 2011). As an undergraduate in Manchester, I had studied the biblical languages and had been quite thoroughly schooled in the methods of historical criticism. These were the methods I took into my doctoral research at Sheffield, though my contemporaries there all seemed to be doing much more interesting things with the biblical texts in conversation with a variety of postmodern theorists (whose work I had also never read). When I subsequently began teaching, it was historical-critical approaches that were the basis for my lectures, not so much because I thought that this was the only right way to teach Scripture in a theological college (something I would seriously question now), but because these were the only approaches I really knew.

It did not take me long to realise that such approaches were not only alienating to many of my students, but had started to become more than a little dry and tedious to me. This subjective impression perhaps had more to do with a prevailing sense of listless exhaustion (mercifully long past) than with any substantial objection to historical criticism as such, but there was an inescapable sense of something missing. Despite the context in which I was teaching, and despite the fact that I regularly preached—as I still do—from the lectionary, it had never occurred to me to engage theologically with the biblical texts in the classroom, to read them as Scripture, partly no doubt because that was not how I had been taught. Equally, it had never occurred to me to approach the biblical texts, in my research and teaching, as literary works (let alone to try and join the dots between the different approaches, which is a vitally important task in a field that at times seems to be made up of a series of echo chambers, each as convinced as the next that its own terms of debate are the right ones).

It should have done, of course, as I certainly was familiar with some of the works of David Clines (I had, for example, read his 1976 monograph I, He, We, and They: A Literary Approach to Isaiah 53 as an undergraduate) and David Gunn (I discovered his brilliant 1980 work The Fate of King Saul: An Interpretation of a Biblical Story while preparing lectures on the books of Samuel), and there is in any case no excuse for being so badly read, especially in major works published so long before. I suspect, however, that I had somehow acquired the prejudice against literary approaches that was unfortunately once quite common amongst orthodox practitioners of historical criticism, as if reading the biblical texts for their literary qualities was either to avoid the real intellectual rigours of historical criticism, the painstaking task of setting the biblical texts in their ancient contexts and reconstructing their literary genesis and growth, or alternatively to mis-categorize the biblical texts altogether, to read them as something they were not.

Reading The Art of Biblical Narrative, however, changed my entire sense of what I was reading when I read the Bible, and brought the narratives of the Pentateuch and the Former Prophets to life for me in a way that most works of biblical criticism—with a few notable exceptions—simply never had. To take one brief but particularly vivid example, Alter’s grasp of the use of dialogue, and layers of diction, in biblical narrative brilliantly captures the way that Jacob and Esau are characterised in Genesis 25:29-34, the cold, calculating Jacob exploiting the animal appetite of the desperate and barely articulate Esau to procure his brother’s birthright. Thus are we drawn by this brief and spare narrative to wrestle with the moral ambiguities of biblical characters who, in the hands of less sensitive commentators, can appear one-dimensional and wooden. And so I began to incorporate Alter’s insights into my teaching and research—I read The Art of Biblical Narrative just in time to teach a paper on the Pentateuch—and I have never looked back.

Esau and Jacob. Matthias Stom.

Alter has since published other works on the literary artistry of the Hebrew Bible, including the monographs The Art of Biblical Poetry (1985; 2nd ed. 2011) and The World of Biblical Literature (1992), and a volume co-edited with Frank Kermode entitled The Literary Guide to the Bible (1990). He has also published, in separate volumes, annotated translations of various books of the Hebrew Bible, including Genesis: Translation and Commentary (1996), The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary (2004), The David Story: A Translation with Commentary of 1 and 2 Samuel (1999), Ancient Israel: The Former Prophets: Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings: A Translation with Commentary (2013), The Book of Psalms (2007), The Wisdom Books: Job, Proverbs, and Ecclesiastes: A Translation with Commentary (2010), and Strong as Death is Love: The Song of Songs, Ruth, Esther, Jonah, and Daniel: A Translation with Commentary (2015). Now, at last, we have what is perhaps the crowning achievement of this great literary scholar’s distinguished career: a complete annotated literary translation of the entire Hebrew Bible in the form of a three-volume boxed set (2019), corresponding to the three divisions of the medieval Hebrew Bible: The Five Books of Moses (Torah), Prophets (Nevi’im), and Writings (Ketuvim). It is this sumptuous, magnificent work that concerns me here.

It goes without saying that all biblical scholars, and indeed all serious students of the Bible, need to engage with Alter’s magisterial translation and the extensive annotations that accompany it, which illuminate the text without burdening the reader with tedious and confusing detail. It has already been widely, and on the whole appreciatively, reviewed and has been followed by a further short work, The Art of Biblical Translation (2019), a succinct and engaging overview of Alter’s approach to translation that extends some of the insights found in the general introduction to the larger work, and in the introductions to the individual books.

My aim here is not simply to add another review, but to ask a quite specific question:

how should Christian readers respond to this work, readers whose scriptures extend beyond the Hebrew Bible, and whose peculiar approach to these texts, not as literary works but as the canonical witness to divine revelation, begins with an encounter with the risen Christ expounding Scripture on the road to Emmaus?

Supper at Emmaus. Caravaggio.

As it happens, Alter’s complete translation of the Hebrew Bible was published shortly after another sole-authored translation, this time by the Christian Old Testament scholar John Goldingay, whose The First Testament: A New Translation saw the light of day in 2018. Unlike Alter, Goldingay is unambiguously addressing Christian readers (The First Testament is published by InterVarsity Press), especially those who need to be jolted out of a complacent familiarity with perhaps less demanding translations. Everett Fox had earlier produced The Five Books of Moses (1995) and The Early Prophets (2014), available in the Schocken Bible series, influenced by the approach to translation of Martin Buber and Franz Rosenzweig. There have also been two major recent sole-authored translations of the New Testament, N. T. Wright’s The Kingdom New Testament: A Contemporary Translation (2012) and David Bentley Hart’s The New Testament: A New Translation (2017). We also now have Ed Greenstein’s Job: A New Translation (2019), which reflects not only Greenstein’s profound grasp of the poetry of Job in the context of the languages and literature of the ancient Near East, but also his distinctive understanding of the original order and shape of the book (for example, readers unfamiliar with Greenstein’s work may be surprised to find Job 4:12-21 at the end of Job’s opening discourse, rather than as part of Eliphaz’s subsequent response).

The Vision of Eliphaz. William Blake.

In their different ways, Goldingay and Alter are both trying to address, and to go some way towards solving, a problem that inheres in all English translations currently on the “market” (a term I use deliberately, but advisedly). They are all, more or less, unfaithful to both ancient Hebrew and modern English, in different ways and to different degrees. In Alter’s opinion (for which there is more than a little justification), “in the case of the modern versions, the problem is a shaky sense of English,” and “in the case of the King James Version, a shaky sense of Hebrew” (in other respects, Alter is highly appreciative of the work of William Tyndale and the later translators of the KJV). Alter’s aim is to do justice to the “semantic nuances and the lively orchestration of literary effects of the Hebrew,” while offering a translation that has “a stylistic and rhythmic integrity as literary English” (The Hebrew Bible, 1: xiii). Goldingay, by contrast, cleaves as closely as possible to “the way the Hebrew (and Aramaic) works” (The First Testament, vii) without undue concern for the literary quality of the English, with results that are both arresting and, at times, necessarily and instructively alienating. To read Alter’s translations of Genesis or Samuel is to be in awe of the literary genius of their ancient authors, whereas to read Goldingay is at times to be stopped in one’s tracks by the strange otherness of it all.

Alter takes pains to reproduce key elements of the Hebrew literary style, in a way that does not lead to barbarousness in English. Wherever possible he retains, for example, the repetition of significant terms in the Hebrew where other translators might be tempted to translate according to context, and where good English style would normally require elegant variation (except where the difference in semantic range between Hebrew and English terms makes this impossible, as proves to be the case with adamah, whose most basic meaning is “soil,” and nefesh, which has all sorts of related senses from “lifeblood” to “person” to “very self”). He seeks to represent faithfully stylistic techniques such as syntactical inversion, as, for example, in Genesis 12:7 where the LORD significantly says “To your seed will I give this land” (italics mine; see also Genesis 16:8; 42:36). Note here also Alter’s preference for the earthier term “seed” (Hebrew zera), where Goldingay prefers the extended sense “offspring,” arguably obscuring the way that the narrator exploits the various nuances of the term throughout the book of Genesis as a whole (the NRSV uses “offspring,” but puts “seed” in a footnote). Words that are chosen by the ancient author for their vividness, such as vattashlekh, “and she flung” in Gen 21:15, are not softened in Alter’s translation as they tend to be in others (likewise Goldingay, “she threw,” in contrast with NRSV, “she cast” and the remarkably bland “she left” of the NJPS). The result is a rendering of the Hebrew that has great immediacy and power.

Hagar in the Wilderness. Camille Corot.

Examples could be multiplied, but I would not wish to spoil your own discovery of the riches on offer here. There are also, of course, places where Alter’s translations, or his annotations, might be questioned—I wonder, for example, whether he is too quick to exclude the homoerotic from Jonathan’s “love” for David in 2 Samuel 1:26 (The Hebrew Bible, 2: 311; I have puzzled long and hard over this verse, and am still not sure I have really grasped it), and it is surprising that in Job 42:6 (The Hebrew Bible, 3: 577) there is a translation that seems to owe more to the influence of the KJV than to the Hebrew itself, with no note about the serious ambiguities of the Hebrew, leaving the impression of a compliant and repentant Job (Greenstein, for one, could not disagree more at this point)—but that is in the nature of the interpretation of these richly ambiguous works, and part of the joy of biblical scholarship is in the give-and-take of thoughtful disagreement about their meaning.

The place of Alter’s translation is perhaps unlikely to be at the lectern (though there may be a case for this—Alter shows greater awareness than most translators of the fact that the biblical texts were written to be read aloud and heard, not perused silently), and I doubt that many churchgoers will be taking this heavy and expensive boxed set along with them to worship (something I think I might encourage them to do, by contrast, with Goldingay’s translation, and certainly with Bentley Hart’s arresting rendering of the New Testament). I do, however, think that Christians need to read it, indeed to immerse themselves in it. There are several reasons for this, all to do with the spiritual, moral, and intellectual health of the Church (notwithstanding the fact that this was hardly the reason Alter produced his translation in the first place).

To begin with, we need to think again about what the Old Testament is, and an intentionally literary translation, which is not obviously constrained by any particular theological assumptions, may be of great help here. It may help us to realise that the ancient authors and tradents of the scriptures, whoever they may have been, were often artists of remarkable creative skill (though I am not entirely convinced that whoever was responsible for 1 and 2 Chronicles was quite in the same league as the genius responsible for the mesmerising narratives of 1 and 2 Samuel, still less those who penned the incomparable poetry of the Song of Songs or Job), whose work has an integrity of its own quite apart from its later appropriation as part of the canon of Christian Scripture. Moreover, the literary artistry of the Hebrew (and Aramaic) texts was itself a vehicle for wrestling with profound theological problems, rather than for proclaiming their resolution. It is, to some extent, the very incompleteness of the biblical texts, their openness to new and unexpected meanings, that keeps them alive for generation after generation of readers and hearers scarcely dreamt of by their ancient authors.

This relates to perhaps Alter’s most fundamental misgiving about modern translations, what he calls “the heresy of explanation,” a tendency he blames on the relative lack of literary sensitivity on the part of the learned philologists responsible for much of the scholarship that finds its way into modern translations, combined with a sense that the Bible, due to its canonical status, “has to be made accessible—indeed, transparent—to all” (The Hebrew Bible, 1: xv). If Alter is right (and I think that, for the most part, he is), then paradoxically a pious reverence for the Bible may lead us to misrepresent it by obscuring something integral to its character, thereby turning it into something that it is not. What gets lost here is the essence of at least some of the biblical texts as works of literary art, whose readers need to be attuned to their nuances and ambiguities rather than seeking out some sort of premature resolution that will tell us, in no uncertain terms, what God wants us to think.

Literature in general, and the narrative prose of the Hebrew Bible in particular, cultivates certain profound and haunting enigmas, delights in leaving its audiences guessing about motives and connections, and, above all, loves to set ambiguities of word choice and image against one another in an endless interplay that resists neat resolution (The Hebrew Bible, 1: xv).

Perhaps we need, then, to be more ready to read Scripture as we might Gerard Manley Hopkins or T. S. Eliot, works of profound theological seriousness whose enigmas and ambiguities are there to keep us guessing, waiting for the moment when they might suggest a fresh way of seeing things that could not have been thought of before.

There is also the matter of the level or levels of style—that is, the register—that we find in the Hebrew Bible, a matter that Alter is one of the few biblical translators seriously to address (The Hebrew Bible, 1: xxiv-xxvii). I sometimes have to explain patiently to people that I do not “speak” Biblical Hebrew (indeed, as Edward Ullendorff argued long ago, “biblical” Hebrew can hardly be categorised as a language as such at all), though I can understand it more than tolerably well (with due reference to the standard grammars and lexica). Not only is there a significant difference between the Hebrew of the Tanakh and the artificially revived and now thriving language spoken on the streets of Tel Aviv, but we cannot be sure what the living dialects of ancient Israel and Judah actually sounded like, nor can we be sure how much of them is preserved in the Hebrew Bible. There is a strong case to be made for the view that much of the Hebrew Bible reflects a higher register of the language than would have been spoken colloquially during the Iron Age in the villages of the Cisjordanian highlands (after all, the biblical texts were written and transmitted by a relatively privileged class of scribes), and this is taken on board in Alter’s translation, whereas it is more or less ignored in others. Perhaps we ought to expect the scriptures, when they are read in study and devotion, to reflect a level of style appropriate for high literature, and, indeed, for sacred worship, leaving room for the fact that at times the biblical texts confound this very expectation by employing a rather more pungent layer of diction (consider, for example, the memorable narrative of Ehud and the King of Moab in Judges 3:12-30, with its clever use of wordplay and decidedly scatological humour). Perhaps, then, we might be expected to work as hard to understand the scriptures well as we would to understand Shakespeare, rather than expecting a single, transparent, accessible meaning to fall effortlessly into our lap.

Here, perhaps ironically, Alter’s translation may be seen to have something important in common with David Bentley Hart’s recent translation of the New Testament. Bentley Hart explicitly aims to represent the roughness of the idioms of the Greek New Testament, refusing to smooth the language out artificially to satisfy the arguably misguided expectations of refined modern readers. What Alter and Bentley Hart show, by virtue of their very different translations, is that the works collected in the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament are on the whole (and with certain notable exceptions) written by, and addressed to, very different sorts of people, something that careful attention to literary style and register ought to make abundantly clear.

There is, however, a more visible and obvious distinction between Alter’s Hebrew Bible and Bentley Hart’s New Testament, and that is that the former is a literary translation of the Jewish scriptures, shared as they are by Christians and culturally influential far beyond the households of faith by virtue of their transmission within the Christian canon, whereas the latter is a non-literary translation of scriptures that are unique to the Christian Church. That is a very good reason, though, for Christians to pay attention to Alter’s work, for these are texts that were not written for us, and have cultural and moral significance far beyond our reception and use of them. This ought to open up rich possibilities for dialogue with those who share these remarkable works with us. It should also serve to put us firmly in our place.

I would like to suggest, furthermore, that the translations of Alter and Goldingay should force us to rethink our relationship, as Christians, with the Hebrew and Aramaic texts that too many of us have either never read, or have forgotten how to read. There is something of a paradox here, in that the significance of these translations is, I think, to send us back to the original. In reading them, we should be confronted with a sense that no translation, not even one as beguiling as that of Alter, can replace the original. It can only represent it, and in representing it, it becomes a fresh work of literature in its own right. To really understand it, we need to cease leaning on the crutch of translations, and to go back to the Hebrew and Aramaic originals (as well as the Greek and Syriac versions in which the Church received and transmitted them).

In an important recent book, The Old Testament is Dying: A Diagnosis and Recommended Treatment (2017), Brent Strawn has charted the demise of the Old Testament in the preaching life of the churches in the United States, a pattern that is familiar to me from certain other parts of the world (over the past couple of decades I have been more familiar with England, Wales, Barbados, and New Zealand, though I would by no means want to claim that my experience has been representative of what might be going on elsewhere), and urged its recovery, for the sake of the spiritual health of the Church. The fundamental fact of the matter is that, for Christians, the Old Testament contains the language of our faith, the language that Jesus spoke to his disciples on the road to Emmaus, the language that provoked their hearts to burn within them as they were confronted by the truth of things in the words of the risen Christ. We ignore or devalue it to our utter impoverishment.

Christ at Emmaus. Rembrandt van Rijn.

There is perhaps a degree of tension between the literary character of Alter’s translation and the theological function of the biblical texts qua Scripture. This tension, though, has the character of a paradox rather than a contradiction. The biblical texts are both literature and Scripture, and there is perhaps a case for being wary of allowing the one to impinge too far on the other: they can be read as either literature or Scripture, though this might in a sense entail that they are both and neither at one and the same time. Yet the literary artistry of the biblical texts can often be seen as a vehicle for their theological meaning, something that is perhaps clearer to see in the Psalms and Job than in, say, the Hebrew text of Esther (which notoriously, and a little confusingly, makes no explicit mention of God). Consider, for example, Job 13:15, where the concise Hebrew hen yiqteleni lo ayachel contains what is surely an intentional ambiguity: is Job saying “Look, He slays me, I have no hope,” or is he saying “though He slay me, I will hope for Him” (Alter, The Hebrew Bible, 3: 498)? In the ancient tradition of reading the text aloud, known in Aramaic as the qere or qeri, the Hebrew allows both, thus drawing the hearer into the very heart of Job’s dilemma: is he abandoning all trust in this God who seems to have gone rogue, or ought he to persist in this trust despite the fact that God seems to be behaving as his enemy? So Christians have every reason to return to the Hebrew Bible and engage seriously with it as a literary work, not least for theological reasons.

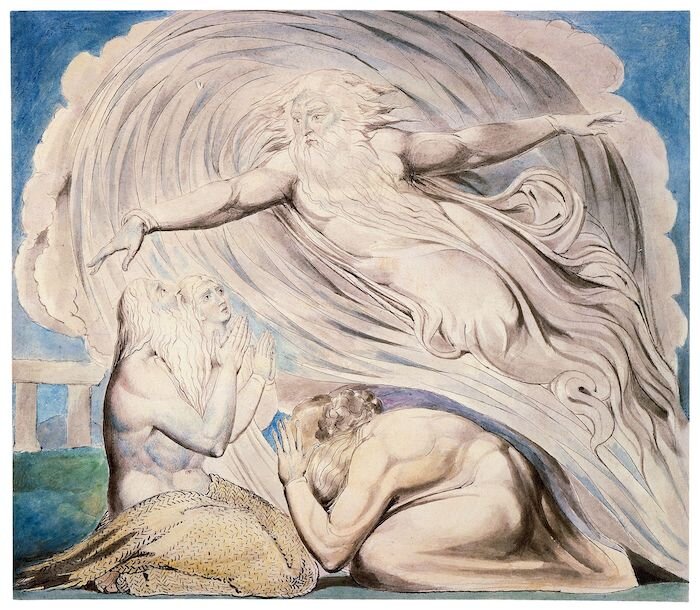

The Lord Answering Job Out of the Whirlwind. William Blake.

Fundamental to the formation of every person called to preach in the Church, and therefore of every ordinand, ought to be deep engagement with Scripture and the Tradition of the Church, framed by a regular discipline of prayer and the Eucharist. This may seem obvious, but it disturbs me how often these days people seem to be ordained and licensed to preach without this fundamental scriptural grounding. It seems to me that the Church needs to be giving far greater attention to the Old Testament full stop than it currently seems to be. This must begin by giving those responsible for preaching and teaching a decent grounding in the scriptures and the languages in which they were first written (Hebrew, after all, is not as difficult as some would like to make out, and it is more than worth the effort to learn it), and then giving them the time and space throughout their ministries to continue to learn. Otherwise, what gives them the right to teach and preach, and why should anyone listen to what they have to say?

It isn’t entirely clear to me why there is such neglect. Is the Old Testament perceived as too alien, too ancient, too peculiar, too morally problematic for us enlightened modern readers? Yet it is the divinely chosen witness to the truth of God’s work with Israel, and in Jesus Christ, and Christians have no place claiming authority over it. In many cases, it is surely meant to shock (Robert Jenson’s justly unsettling commentary on Ezekiel brings this quality out particularly well). Is the Old Testament less evidently applicable to the lives of modern Christians than the New Testament, dare I say it, less “relevant” (an adjective of dubious value for the Christian life), or even less “useful” (quelle horreur)? Yet the life and teaching of Jesus and the Apostles have no meaning outside the language of the Hebrew Bible, and to relegate it in favour of the New Testament not only ignores this inescapable fact but risks aligning the Church far too closely with the long, sordid, and unutterably tragic history of Christian anti-Judaism. Is the patient study of Scripture perhaps perceived to be less pressing for the Church than the formation of practitioners fit to engage actively in “mission”? If so, then there is a false dichotomy at work, for the mission of God in and through the Church—however we might define this (and in my more cynical moments I am more than a little reminded, when the word “mission” is mentioned, of the grotesquely earnest guests at the wedding of Caddy Jellyby and Prince Turveydrop in Bleak House)—entails a deep and abiding familiarity with Scripture, in all its compelling and difficult oddness. For this is how we know what the mission of God is, and, by extension, who we are.