Discerning a Calling to Ordained Ministry

‘To learn how to pray and to die’

If you were looking for a reason to be put off ordained ministry, you could do worse than pick up your nearest Book of Common Prayer. In the Ordinal, very probably written in the summer of 1550, Thomas Cranmer elucidated the role of priests as those who are

to seek for Christ's sheep that are dispersed abroad, and for his children who are in the midst of this naughty world, that they may be saved through Christ for ever.

It’s not the prospect of a naughty world that unnerves (though it clearly has its charms) so much as his account of how ‘great a treasure’ is committed to the charge of the priest in the ministry of seeking, teaching, and warning. Far from being a professionalized jolly presence in rural England à la Dawn French, or some vaguely spiritualized form of social services, Cranmer’s preface startles with its radical reference to salvation. Frankly, it ought to leave every ordinand (and every priest returning to their source texts), deeply fearful; ultimately, the threefold ministry of bishop, priest, and deacon is directly concerned with matters of eternity and our everlasting enjoyment of the presence of God. Little wonder that Cranmer takes great care to urge the ordinand carefully to

consider with yourselves the end of your ministry towards the children of God, towards the spouse and body of Christ; and see that you never cease your labour, your care and diligence, until you have done all that lieth in you, according to your bounden duty, to bring all such as are or shall be committed to your charge, unto that agreement in the faith and knowledge of God, and to that ripeness and perfectness of age in Christ, that there be no place left among you, either for error in religion, or for viciousness in life.

In a Church that has in recent years taken great efforts to delineate the skills and techniques of ministry (the egregious ‘learning outcomes’ that haunt many a curate), Cranmer’s words seem ripe for retrieval. Their force was echoed in a lecture I heard not so long ago by Rowan Williams, who was asked by a group of young learned clergy to describe what it was the priest actually taught (hoping perhaps for an answer of such sophistication to justify their malingering in our finest universities). After a short pause and a raised eyebrow, +Rowan gently ventured: “to teach people how to pray and how to die”.

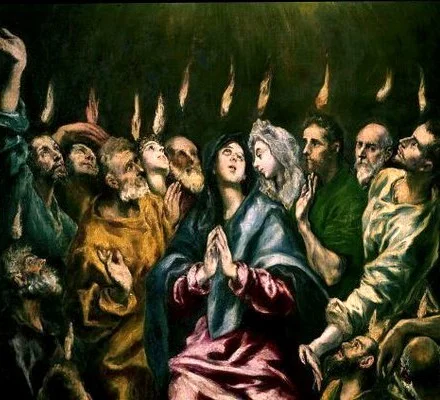

Grace

How could anyone feel qualified for such a ministry?

Relief lies later in the Prayer Book’s liturgy, where the bishop urges the ordinand that the

will and ability is given of God alone. Therefore ye ought, and have need, to pray earnestly for his Holy Spirit.

That is, the call and capacity to exercise this particular ministry within Christ’s Church flows from the work of the Spirit—the selfsame who, in our baptism, allows us to address God as Abba. All our callings find their origin and end in his creative work. Far from emerging from a proud confidence in our own capacity to preach, teach, or to offer better pastoral care than our vicar (for example), the fullness of life promised by Christ emerges from abiding in the ceaselessly creative love that flows between Father, Son and Holy Spirit. To use the imagery of Gospels, this life is to be found—with the Beloved Disciple—resting peacefully on the breast of our Lord (John 13.25) rather than anxiously trying to control our future like Judas; or sitting with devotion with Mary at Christ’s feet—listening, contemplating, waiting—rather than proving our worth with any number of well performed tasks like Martha (Luke 11.38-42). Note, in particular, the resonant exchange of questions when Jesus calls his first disciples in Gospel according to St John (1.35-38):

The next day John again was standing with two of his disciples, and as he watched Jesus walk by, he exclaimed, “Look, here is the Lamb of God!” The two disciples heard him say this, and they followed Jesus. When Jesus turned and saw them following, he said to them, “What are you looking for?” They said to him, “Rabbi” (which translated means Teacher), “where are you staying?” He said to them, “Come and see.”

For the disciples, the question of what they are looking for finds its answer in their desire to be where Jesus is, where he abides, even though the way there is not described. Jesus offers no manifesto, no rallying cry, no details of his teaching. He says simply, ‘come and see’. As we know, the way to where he abides will only be found through the Cross, a fact the disciples will learn only after a great deal of incomprehension, pain and grief (cf. John 14) as they themselves learn to inhabit with the mystery of Christ’s passion. If the ordained are, like John the Baptist (John 1.35-36), to point eagerly to Christ as the Lamb of God (Look!), they too can only do this if they themselves have taken care to ponder deeply Christ’s question, ‘What are you looking for?’ and to reply with their whole being, “Lord, show me where you abide and give me the courage to follow you there, even through the times of pain, incomprehension and grief.”

All of this is to say that to the call to be ordained must, like the disciples, flow not from confidence in our competence, wisdom or strength, but from our own experience of grace – that, in Jesus Christ, we have discovered wealth in our poverty, strength in our weakness, joy in our tears, and life in death.

Ministers of the Resurrection

It is perhaps not so surprising, therefore, that very often people feel drawn into the path of the apostles after experiencing some kind of trauma, having vividly experienced for themselves the power of the Resurrection to bring light out of darkness. Even when the call has not emerged so dramatically, to be ‘heralds of the Kingdom’ (as it is written of deacons) who can ‘discern the signs of God’s new creation’ (of priests) suggests people able to testify with every fibre of their being that ‘in Christ there is a new creation’ (2 Corinthians 5.17)—that Christ is indeed triumphant and death has lost its sting.

In this sense, I have been particularly struck by the description of priests by Benedict XVI as ‘those who make the Resurrection present’. Preaching in 1979 on the feast of the Blessed Maximilian Kolbe, the then Joseph Ratzinger reflected how he had had the privilege of sharing the Eucharist with Pope John Paul II in Auschwitz-Birkenau in the week after Pentecost:

It was an exciting thought and an exciting experience, over this vast harvest field of death, on this killing field on which over a million people met their death, to live to see the presence of the Resurrection as the only true and only sufficient answer to it…to experience how this memorial to hatred and inhumanity became a place of the triumph of love of Jesus Christ and of love…;[through the Mass], the pope could interpret the former scene of the most profound debasement of man as the place of the victory of love, where the power of Jesus Christ’s love proved stronger than all destruction of things human. [1]

It is a wonderful account of how the priest bears a treasure beyond human understanding (‘foolishness to the Greeks’, as Paul put it), of how the Eucharist of the Lord is at the very heart of the priestly ministry as the source of all our mission and evangelism and the lens through which we interpret all life and death, even the world’s worst horrors. As he continues:

Giotto, Noli me tangere. Scrovegni Chapel, Padua

Making the Resurrection present means that we ourselves live in it and on it. It can happen properly only if we are acquainted with the risen Lord. When the first election of an apostle was to be made in the Church after Easter, the fundamental criterion was: the one so appointed must know Jesus Christ, must have sat at table with him, must have been one of his followers, and must have met the risen Lord. [2]

To be called into the apostolic ministry is to find oneself knowing the risen Christ, accompanying him on his paths, learning to recognize his voice and, so encountering him, learning how to make the Resurrection present to a world otherwise mired in death and decay.

Listening, recognizing, and encountering

Thus far, I’ve suggested that to be drawn into the ministry of the Resurrection flows from the irresistible freedom and joy we discover, utterly unmerited, in the presence of Jesus – that fullness of life that finds its ultimate expression in the Holy Communion.

This raises all sorts of questions then about how we go about the business of discernment and, indeed, training of the clergy. Much of the contemporary advice is ‘give it a go!’ and see what it feels like. I can see much value here, but I sometimes wonder whether that’s putting the cart before the horse. While we might naturally suggest people exploring ordination ought to write essays, go on placements or preach homilies, discernment primarily emerges from drawing near to Jesus and seeking to know him better; and, knowing him better, learning to discern his presence more readily in the eye of the stranger, the naked and the prisoner, and in the dark and forgotten corners of our world as much as in books.

For example, I recently met with one of our finest young ordinands in Chichester who, when I asked him where he had encountered Christ most vividly since our previous meeting, told me of how—surprisingly—it was in the face of a man in Brighton’s homeless community as he tried to punch him. At first sight the story seemed very odd but, as he unfolded it, it became clear that he had a genuine gift for discerning and pursuing the risen Jesus in his midst, even in the face of a violent man. He went on to recount how he had since gone on to open up the Scriptures to the same man, whose appetite for knowing Jesus was voracious.

How might we train our sight to discern the Resurrection at work in our midst in this way? How might we find ourselves drawn into this pattern of watching and waiting for the signs of God’s new creation breaking in around us?

Although the Church of England has developed over a hundred training pathways for her ordinands to hone their abilities in this respect, the core is essentially simple. Think back to the disciples on the road to Emmaus, whose dullness of sight was relieved by the opening of Scripture and the breaking of bread. If people feel called to the ministry of making the Resurrection present in our own day, I cannot underline enough to them the value of:

- The Daily Office and the Study of Scripture:

Jesus explained to them what was said about himself in all the Scriptures. He began with Moses and all the prophets (Lk 24.27)

Canon Law requires clergy to say the Daily Office precisely because it is the lens through which they might interpret the work of God in their daily life. While ignored by some clergy as rather stodgy, what better way is there to open and close the day by saying the prayers that Jesus himself prayed (the Psalms), by hearing of the work and promises of God in the Old Testament and acclaiming their glorious fulfilment in the New. It may take ten years before you can realize the full power of the Daily Office as a pattern for your life, but how can one discern the work of the Spirit in the world if you are not acquainting yourself with God’s works in ages past? Similarly, how much time are you taking to go deeper into the Scriptures with commentaries and further study? Have you even read the whole Bible—an easy task given the abundance of apps available for this purpose nowadays?

- Eucharistic Devotion:

They told how they had recognized Jesus when he broke the bread. (Lk 24.35)

If the Eucharist is at the heart of the ministry of the Resurrection, are you regularly seeking the Presence of Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament? If you communicate weekly on a Sunday, perhaps you might like to think about setting aside more time to draw closer to Him in making a mid-week, or even daily, Communion, and in seeking his company in silent contemplation before the Blessed Sacrament. The importance of silence around the Eucharist and due preparation before the Sacrament (fasting and prayer, for example) cannot be underestimated if one is to allow the liturgy to be a vehicle for receiving the life and love of the triune God. Draw near to God, and he will draw near to you (James 4.8).

- Shared Discernment and Spiritual Direction

They said to each other, ‘Were not our hearts burning within us while he was talking to us on the road, while he was opening the scriptures to us?’ (Lk 24.32)

Seeking and discerning the new creation is not a solitary endeavour, but is undertaken when two or three are gathered together in our Lord’s Name (Mt 18.2). It’s precisely for that reason that discerning a vocation is never a private affair but is a shared task of the Church (expressed through diocesan discernment processes and the Bishops’ Advisory Panels). It’s also why a spiritual director is so important for the journey of discernment – someone one step removed from your regular church life who might reflect with you on the burning presence of God in your life and how best you might respond with more confidence to our Lord’s invitation, ‘Come and see!’. This might take the form of exploring new forms of prayer, such as Lectio Divina or use of the Examen (an Ignatian practice for reflecting upon the presence of God during your day). Most dioceses will have a network of spiritual directors; ask your parish priest or chaplain for more information.

I sense a call to ordained ministry. What next?

If by drawing nearer to the risen Jesus in this way you feel an irresistible and persistent draw to making the Resurrection present in the world through Word and Sacrament (this ‘weighty office’), what are the next steps? For many, the sense of being called to ordained ministry feels surprising, often terrifying, and appears as an unwelcome interruption to an established pattern of life.

If God is calling you, he’s unlikely to stop. Given the significance of the call, however, you must be both courageous and wise in how you respond. Courage is required in having that first conversation with your partner or parents and your priest. It seems to be one of the hardest moments in the discernment process, since you make yourself very vulnerable by articulating it. Accordingly, wisdom is required in deciding when and how you share your sense of calling, and with whom. You might like to talk at some length about that with your spiritual director first: ‘going public’ comes with a certain cost, particularly in relation to the wider congregation, so tread carefully and stay close and seek the advice of those you trust, particularly those you know to be close to Jesus themselves.

If your parish priest or chaplain is supportive they will more often than not give you something to read, or invite you into a deeper involvement in the liturgical and teaching life of the parish (in service at the altar, for example, or training you to preach a short homily at a midweek service). Usually, when they feel the time is right, you will be encouraged to speak with someone in the vocations team of your diocese. This normally signals a change of gear, not least as you find yourself becoming acquainted with an ever-increasing range of Church of England jargon. In the company of the diocesan director of ordinands (DDO) or one of their assistants, you will together seek to discern whether your sense of call to ordained ministry is realistic, informed and obedient, as defined through the nine Criteria for Selection for Ordained Ministry in the Church of England.

Understandably, it’s a lengthy process of conversations, interviews, reflection, often placements in other churches and usually lasts at least eighteen months. If your bishop is willing to support discernment at a national level, you will eventually be sent to a Bishops’ Advisory Panel (BAP), a three-day residential conference consisting of worship and prayer, three interviews with national Advisers, presentations and group work, and the writing of a pastoral letter. In advance of this, a range of references are sought, and you are invited to write a reflection on your engagement in mission and evangelism in your own context as well as complete a lengthy registration form. In some dioceses too you might be asked to go into greater detail around the criteria around Personality and Character and Relationships with a trained psychotherapist, whose report will feed into the preparatory papers for the BAP. While this might all seem arduous, the underlying intention is a prayerful exercise in listening to the will of God - for the glory of God and for the good of His Church.

How are ordinands trained?

If the Advisers recommend to the Bishop that you are ready to enter training for ordained ministry, you will normally embark upon two or three years of formation – either full or part-time - at one of the Church’s theological institutions, depending on your age, prior learning and experience. It also depends on whether you are offering yourself for full-time stipendiary ministry or part-time self-supporting ministry (usually alongside other employment or work in the local community). The right pathway for you is worked out with your DDO and your sponsoring bishop.

At the end of your college training, the Bishop ordains you as a Deacon, usually serving in this order for a year prior to ordination to the Priesthood (although a small number of people feel God is calling them to the distinctive diaconate). From ordination as a Deacon, you spend three to four years serving in a parish as an assistant curate, working alongside an incumbent in a parish different from the one that sent you.

Conclusion

While the calling to holy orders is weighty and often terrifying, it is made possible by the grace of the Holy Spirit, who enables men and women to make the Resurrection of Jesus Christ present through the ministry of word and sacrament. If ordination is sought out of a desire for power, titles, robes or poorly insulated Victorian vicarages, you will invariably find yourself as fulfilled and attractive as the Scribes and Pharisees (Luke 20.46). Rather, those called to this ministry are, like the first apostles, shaped by their encounter with Christ, who leads them irresistibly to be heralds of his kingdom. They will have a delight in His company that enables them to help all God’s people discern the new creation burgeoning in their midst, even among the most unlikely people and in the strangest places (Behold, the Lamb of God!). If God is calling you this way of life, what is holding you back? What are you looking for?

Benedict XVI, Teaching and Learning the Love of God: Being a Priest Today (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2017). p. 94.

Ibid, p. 95