A Christian Vocation: Chaplaincy in the Armed Forces

Our on-going series on Christian vocation continues with a piece on the particular calling to military chaplaincy. The Venerable Barry Hammett CB, QHC was Chaplain of the Fleet, Director General of the Naval Chaplaincy Service and Archdeacon for the Royal Navy from 2002 to 2006.

For centuries the basic unit of Church life has been the parish, and parochial ministry is still today the principal focus for the work of the clergy and committed lay people. But it has been widely recognized in recent times that there are areas of life that demand a more specialized form of outreach, and this in turn has led to the development of a wide range of so-called “sector ministries” of which Chaplaincy in the Armed Forces is one, albeit of greater antiquity than most.

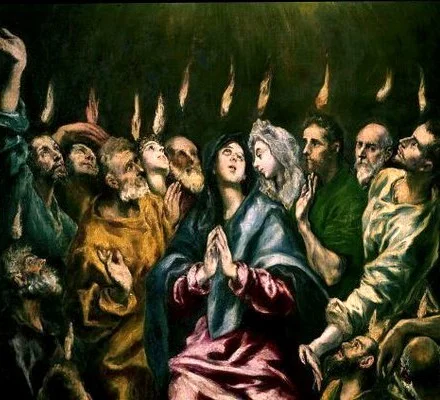

This form of the Church’s ministry came to be most highly valued during the wars of the twentieth century. On the wall of my study I have a copy of a painting by Terence Cuneo depicting King George V investing the Reverend Theodore Bailey Hardy with the Victoria Cross in a village in France during the Great War—an award recognizing his devotion to duty in rescuing the wounded in the field of battle under enemy fire—and there are many other examples of the commitment and dedication (even to the extremes of giving their own lives for the sake of those whom they served) by Chaplains in both World Wars and other conflicts. In peacetime, too, the Chaplain has traditionally been valued as (to use a naval expression) “the friend and advisor of all on board”.

I spent 29 years as a Naval Chaplain, and so this piece is written from the perspective of the Royal Navy, but most of what I say can be readily related to ministry in the Army and in the Royal Air Force.

Terence Cuneo. Presentation of the Victoria Cross to the Reverend Theodore Bayley Hardy, VC, DSO, MC by HM King George V (1865–1936).

The nature of Chaplaincy

Prince Philip, reflecting on his time as a Naval Officer—a career that he left with great reluctance when he married the future Queen—once said “It’s not quite like any other profession: you are segregated in some way. And you are all equally liable to whatever happens. If something happens to your ship everybody on board is equally liable to get hurt”.

For a Chaplain serving in the front line this level of involvement in the life of the people among whom he or she is set is always a defining characteristic of ministry. When at sea there is no going home for the evening, no opportunity for a day off to escape the demands of day to day life, no chance of going out for a walk to clear the mind (apart, perhaps, from a few turns around the upper deck), usually no-one with whom to share the Daily Offices, no friend in a neighbouring parish with whom the worries and frustrations of clergy life can be shared. Serving in a warship at sea or with an active unit of the Royal Marines is, in my experience, the most truly incarnational form of ministry I have ever known, in that the Chaplain shares fully in the experience of the whole ship’s company—whether it be sea-sickness, separation from home, family and friends, fear when the ship is at action stations or even the pleasure of a fine day on passage to a foreign port—all of them uniquely shared, enjoyed or endured.

And there is a further component in such ministry in that these experiences are shared with a group of people with whom the parish clergy are often least likely to have much contact - young men and women, many from backgrounds that are far from privileged, who have probably never been inside a church building nor ever spoken to a member of the clergy, and who carry in their minds only a stereotype image of what the clergy are like. It is immensely rewarding (and often humbling) to find that though the Church has played precisely no part in their lives they nevertheless often display a hidden and as yet unrecognized faith that is waiting to be nurtured. When there is some crisis, or a tragedy such as the death of a messmate, their need for God and for the ministry and support of their Chaplain comes very much to the fore, and that is when ministering to them becomes a real privilege, and though few will become fully committed and practicing members of the Church, most will return to civilian life with a somewhat changed understanding of the Church and of the clergy that must surely make a positive contribution to the ministry of the Church at large.

Such front line ministry is, however, only a part of what a Chaplain in the Armed Forces does, just as the Forces themselves comprise a variety of functions. In order for activity to take place at the front line there is a huge infrastructure in place for recruitment, training, pay, feeding, housing, career development and discipline, as well as for the acquisition and maintenance of the equipment – from aircraft carriers to socks – necessary to support the work of the front line. Chaplains are typically present in all the places where such functions are undertaken, so that they will find that sometimes they are exercising the ministry of an industrial Chaplain, sometimes that of a school Chaplain, sometimes (in an officer training environment) that of a university Chaplain, sometimes (in a home base with a large Church and a Married Quarters estate) that of a parish priest, as well as in front line ministry itself. A change of appointment every two or three years ensures freshness and variety, as well as growing experience, for every Chaplain. There is no room for other-worldliness on the part of a Chaplain in the Armed Forces. Only a priest who can readily relate to people at every level of the Service, who is robust, confident in faith and capable of a high level of self-sufficiency will make a success of this particular calling. Such demands are also made of partners and families too, since they must be ready to endure periods of separation—often for several months at a time—just like every other Service family.

The theological context

A Chaplain is first and foremost a priest or minister of the Church in which he or she has been ordained and which continues to license or authorize his or her ministry. In recent years this framework has been extended to include Chaplains of other faith—Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu—though the majority continue to be Christian. An Anglican priest is bound by the duty of obedience to the Bishop (in the case of the Armed Forces the Archbishop of Canterbury) and by the duties, responsibilities and expectations laid down in the Ordinal. In this he or she is no different from a counterpart in parochial ministry, however great may seem the difference in the context in which ministry is delivered.

It is, of course, our faith and our conviction that there is no part of God’s Creation from which He is absent, that He is with us and in us at every moment in our lives, the good times as well as the bad. He is there with His people in their joys and their sorrows, at times of virtue and at times of sin, when they are in pain and when they are afraid, as well as in the ordinary business of daily life. The presence of the Chaplain in all the activities of the Armed Forces serves as a sign of God’s presence with them, as a reflection of His love for His people no matter what may be happening in their lives. There have always been those who have sought to suggest that the involvement of Chaplains in the Armed Forces somehow lends legitimacy to acts of war and violence. I would argue that there is no truth in this suspicion. Chaplains have often had concerns about the morality or the justice of the action in which their people are involved, about the decisions that are made or about the way in which others are treated, and it would be a poor Chaplain who did not voice those concerns with the persons responsible. This may not make for popularity, but it usually engenders respect, and it is faithful to the responsibility to admonish as set out in the Ordinal. The overriding priority, however, is always to be the sign of God’s unconditional love in the midst of His people.

In the training arena the Chaplain has a particular role in helping to form the capacity for moral decision making by the members of the Armed Forces, essential for the just prosecution of their tasks when the pressure of circumstances requires near instant responses to the issues and problems facing them. It is a key aim of the Chaplain to try to ensure that all personnel are so grounded in the principles of justice, mercy and, indeed, legality that good and proper decision making becomes second nature to them. Moreover, the Chaplain must always be at hand to discuss and talk through with them the moral implications of what they are expected to do, as well as at times to challenge those in positions of authority (not always an undertaking to be relished!) in a way that no-one else in the Service community can do. Service men and women at all levels of authority and seniority are by and large highly morally literate, suggesting that the efforts of Chaplains have not been in vain.

This level of moral literacy can cause considerable soul-searching when individuals are faced with uncertainty about the justice or morality of what they are being called upon to do. I can personally testify, as Chaplain of the Fleet at the time of the invasion of Iraq in 2003, to the unease and anxiety about that venture being expressed at every level of the Naval Service, from junior seamen to senior Admirals, and I know that this was mirrored in the other Services. The Chaplain has a crucial role in helping others to work through such dilemmas and to counsel them without directing their conclusions. Members of the Armed Services must, in the end, feel able to trust those who lead them, and the leaders, in their turn, have to be able to place their trust in the government which is demanding their action. Without that ability to trust at all levels there is the potential for moral disaster.

And of course, in common with all priests, Chaplains have a duty to proclaim the Gospel both in their lives and in the worship of the Church, teaching, preaching, celebrating the sacraments and exercising a ministry of reconciliation.

Conclusion

Like any form of ministry, Chaplaincy in the Armed Forces is a vocation rather than a matter of personal choice. It is a ministry that makes particular demands of the individual in terms of resilience, self-sufficiency and patience, not least in enduring long periods of separation from home, friends and loved ones. Without a true vocation it is unlikely to be bearable, but for those called to such ministry it is a deeply fulfilling experience in which it is a privilege to share.