St John Chrysostom

In celebration of his feast day—September 13—Mark Edwards has written an introduction to the Golden-Mouth's life and thought. Chrysostom is of particular significance to us here at St Mary Magdalen's, because we hear his Paschal Homily every year at the Easter Vigil. Professor Mark Edwards is Tutor in Theology at Christ Church College, Oxford and other of such books as Origen Against Plato and Catholicity and Heresy in the Early Church.

John Chrysostom, whose name is Greek for “Golden-Mouth”, was born to an army officer and his (possibly pagan) wife in 349. He was not baptized until he was thirteen. Furthermore, when he went to study in Antioch—the chief city of Syria and the Levant—he pursued his studies in rhetoric with the pagan Libanius, the greatest master of rhetoric in the fourth century before Chrysostom himself. At the same time, he did consider himself a Christian and embraced an ascetic life which suited his bookish temperament. As he entered his thirties, however, he suffered a misfortune which he never ceased to lament thereafter: a friend who had received ordination persuaded him that he too was called to do likewise. Chrysostom, with the strong encouragement of his widowed mother, fought for a long time against his vocation: in those days, a man quite literally fled from those who wished to lay hands upon him, but it was all to no avail. In 381 he became a deacon and in 386 a priest.

His eloquence drew great crowds to the Golden Church, the cathedral of Antioch, and for more than a decade he repaid their admiration by telling them all that they were heinous sinners, full of the world and empty of righteousness , who squandered on clothes and banquets the money they owed to the poor, while preening themselves on their wealth, their family trees and profane accomplishments that would count for nothing in the Kingdom of Heaven. Some scholars have inferred that the Christian world of Chrysostom’s day must have been unusually lax, but of course the opposite is more likely: it is when a congregation is serious about its religion that it comes back day after day for new castigations, and it is when the pews grow cold that the preacher dares not talk about sin for fear that next week he find himself haranguing an empty church.

Antioch, in size and wealth the third among the cities of the eastern Roman world, was still a home to many pagans, and Chrysostom was dismayed to see professing Christians joining in their festivals and their riotous way of life. His remedy was that Christians should attempt to turn every godless practice that they had abandoned into some Christian analogue; instead of swearing by Zeus in season and out of season, why not pray at all times to God? Instead of getting drunk in some house of disorder, why not hurry to the altar and receive the bread of wine which will unite us with Christ himself? Protestants have sometimes deplored the growing opulence of the fourth-century churches and the explicit transformation of the eucharist into a sacrificial rite whose ministers towered over the people in their vestments; to Chrysostom and his peers, however, there seemed to be no other way if Christianity was to become the religion of the whole imperial population, as the Emperors clearly desired.

No Emperor was more forceful in his decrees than Theodosius I, yet his relations with the church and the Christian populace were not easy, and it was Chrysostom who had to play the mediating role when a riot in Antioch resulted in the defacement of royal statues. On the one hand Chrysostom had to assuage the wrath of his sovereign, opportunely reminding him (unless Chrysostom himself made up the story) that when Constantine heard of the breaking of one of his statues, he merely passed his hand across his face and asked with a smile why he could not feel any scars. On the other hand, his duty both as a subject and as a churchmen was to lead the Antiochenes back to the quiet obedience which was manifestly enjoined on them by scripture. As always, he did not play down their avarice, their vainglory or the perpetual quarrelsomeness which had lured them so quickly into violence; reflecting, however, that many had now suffered disproportionate penalties, he admonished them that scripture does not promise ease to the saints but a life of tribulation, in order that they may be on the road to perfection when they die.

Icon. John Chrysostom.

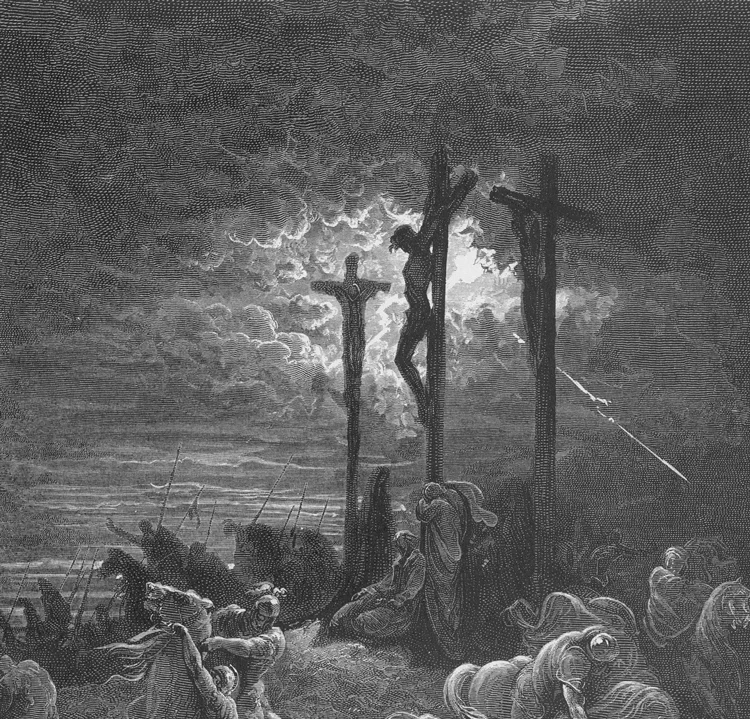

Copious as his preaching was, he rarely intervened in the theological disputes that were tearing apart the Christian population of Antioch. Meletius, the bishop who ordained him as a deacon, was suspected of being an Arian, that is, of not believing that Christ was fully divine. On this matter Chrysostom was unequivocal: Christ was God from God, coeternal with the Father and of one nature with him, as the Nicene Creed of 325 declared. A number of his friends in Antioch were associated with a heretical, or at least dubious, understanding of Christ, which separated his divine and human natures to such a degree that they seemed to have divided him into two sons, one of whom was the Word of God and the other merely Jesus of Nazareth. This error (real or supposed) was rejected with particular vehemence by the bishops of Alexandria, who insisted that the man who is Jesus of Nazareth is also God – in such a strict sense that if we say the man suffered on the Cross we must say that God suffered on the Cross, and if we say that the man was born of Mary we must also say that God was born of Mary. This is indeed the oecumenical doctrine, and Chrysostom proclaimed it as clearly as anyone in his commentaries and sermons. No-one else could expatiate so movingly on the love which God revealed by becoming a creature, let alone by taking on the appearance of our collective sin and accepting on our behalf the work of expiation which he alone did not need to perform. No-one spoke in such august tones of the horror of Good Friday, where the blood that was to purge the world streamed down from the side of the Lord.

At the same time, he avoids any technical formulae that would prove him to be on one side or the other of the great controversy, and, while he says nothing that brands him as an Antiochene, he also says nothing that would have been unpalatable to those who were of that party. Like all the best theologians, he had no interest in metaphysics unless it had some practical application: to know that God came down to be one of us and died to ransom us from our sins is sufficient for faith. We see the same principle in his discourse on the incomprehensibility of God, where he cites famous texts of scripture which had been deployed against heretics and pagans, but in this case not for the sake of winning any doctrinal argument but to illustrate the boundlessness of divine love. In his biblical commentaries also, he is willing to admit that he cannot penetrate all mysteries. His reading of Paul, for example, agrees with that of his predecessors in making human beings partly responsible for their salvation insofar as they must consent to the working of the Holy Spirit; at the same time, he does not allow us to think that there is any power in us which could render us worthy of divine mercy. In a passage which the Elizabethan Homiliesquote with approval, he observes that, while we rightly expect true faith to be accompanied by good works, God also has the power and freedom to save us without works when we lack time to perform them, as he saved the thief on the Cross.

Chrysostom carried his reverence for Paul so far that he alone refused to admit what everyone else perceived with some embarrassment – that Paul, when judged by the educated norm, was a clumsy writer whose prose abounds errors and idiosyncrasies that no trained orator could have perpetrated. Other commentators made the best of his ineptitude, arguing that it was evidence of his probity; when Chrysostom, however, sees Paul losing control of a sentence, he represents this as a deliberate trope. Thoroughly conscious of his own special pleading none the less, he ends each chapter of his commentary on Galatians with a paraphrase of Paul’s bad Greek in his own euphonious manner, and thus removes any lingering cause of offence to the cultured ear. No wonder that tales of his special intimacy with the apostle grew in the telling. At the Council of Florence in 1438 (just over a millennium after his death), the Greeks and Latins disagreed as to whether Paul was teaching a doctrine of purgatory when he said at 1Corinthians 3.15 that the works which a person builds on Christ may be destroyed while the person himself is saved by fire. Chrysostom had interpreted “saved by fire” to mean saved for torment in hell; Augustine was alleged to have held that the fire will be therapeutic and temporary. The Greeks did not need to read Augustine; they simply recalled that a young associate of Chrysostom had once peered into his study and had been amazed the see a figure emerging from the bust of Paul which the master had at his desk. As this figure communed with Chrysostom, the observer perceived with surprise and awe that he was none other than Paul himself.

But those who watch over the saints, as Chrysostom tells us, do not spare them tribulation, and a tongue as sharp is his is all the more dangerous to its possessor when every word that falls from it lingers in the soul. When he was appointed in 397 to the see of Constantinople, he found the women as prodigal and vain as in Antioch, and none more so than the Empress Eudoxia, of whom he proceeded to make an enemy. At the same time, the bishop of Alexandria, Theophilus, was trying without success to discipline a quartet of monks, whom he accused of teaching a heresy (partly of his own invention) which was known as Origenism. The four monks fled to Constantinople and brought their complaints against Theophilus to Chrysostom. Fearing defeat, the Alexandrian patriarch crossed the sea with remarkable alacrity, and held a synod outside Constantinople, at which Chrysostom was declared to have been deposed for his heretical sympathies. No-one was really deceived, and the bishop of Rome intervened at once to countermand the deposition. But the damage was done, for Theophilus had given Eudoxia a pretext to have Chrysostom banished. This measure gave rise to a popular revolt, and he was recalled almost once. He took the opportunity to deliver another fulmination against the Empress’s taste in clothes and jewellery, and this time was banished for life. After his death on September 14 407 a schism festered briefly between his supporters and his adversaries, but in 438 his bones were translated to Constantinople with imperial permission and public acclaim. He died, as he had lived, in affliction, according to his own definition of sainthood, and he is now a saint with two feast-days – the thirteenth of November in the Orthodox world and the thirteenth of September in the tradition that stems from Rome.